denying infant baptism was made a cause of banishment [in Massachusetts], by men who knew that many who did so, did not hold the errors mentioned in this law. And Mr. Cotton said in those times,

“they do not deny magistrates, nor predestination, nor original, sin, nor maintain free-will in conversion, nor apostacy from grace ; but only deny the lawful use of the baptism of children, because it wanteth a word of commandment and example, from the Scripture. And I am bound in christian love to believe, that they who yield so far, do it out of conscience, as following the example of the apostle, who professed of himself and his followers, We can do nothing against the truth, but for the truth. But yet I believe withal, that it is not out of love to the truth that Satan yieldeth so much, but rather out of another ground, and for a worse end. He knoweth that now, by the good hand of God, they are set upon purity and reformation; and now to plead against the baptism of children upon any of those Arminian and Popish grounds, as those above named, Satan knoweth they would be rejected. He now pleadeth no other arguments in these times of reformation, than may be urged from a main principle of reformation, to wit, That no duty of God’s worship, nor any ordinance of religion, is to be administered in his church, but such as hath a just warrant from the word of God. And by urging this argument against the baptism of children, Satan transformeth himself into an angel of light.”*

* Cotton on baptism, 1647, p. 3

An Abridgment of Church History of New England, Isaac Backus

Month: October 2014

Owen: New Covenant Conditional or Absolute?

See also Petto: Conditional New Covenant?

and Owen on Hebrews 8:6-13 Collapsible Outline

Owen on Hebrews 8:10-12

The design of the apostle, or what is the general argument which he is in pursuit of, must still be borne in mind throughout the consideration of the testimonies he produceth in the confirmation of it. And this is, to prove that the Lord Christ is the mediator and surety of a better covenant than that wherein the service of God was managed by the high priests according unto the law. For hence it follows that his priesthood is greater and far more excellent than theirs. To this end he doth not only prove that God promised to make such a covenant, but also declares the nature and properties of it, in the words of the prophet. And so, by comparing it with the former covenant, he manifests its excellency above it. In particular, in this testimony the imperfection of that covenant is demonstrated from its issue. For it did not effectually continue peace and mutual love between God and the people; but being broken by them, they were thereon rejected of God. This rendered all the other benefits and advantages of it useless. Wherefore the apostle insists from the prophet on those properties of this other covenant which infallibly prevent the like issue, securing the people’s obedience for ever, and so the love and relation of God unto them as their God.

Wherefore these three verses give us a description of that covenant whereof the Lord Christ is the mediator and surety, not absolutely and entirely, but as unto those properties and effects of it wherein it differs from the former, so as infallibly to secure the covenant relation between God and the people. That covenant was broken, but this shall never be so, because provision is made in the covenant itself against any such event.

And we may consider in the words, —

- The particle of introduction, o[ti, answering the Hebrew yKi.

- The subject spoken of, which is diaqh>kh; with the way of making it, hn[ diaqhs> omai, — “which I will make.”

- The author of it, the Lord Jehovah; “I will …… saith the Lord.”

- Those with whom it was to be made, “the house of Israel.”

- The time of making it, “after those days.”

- The properties, privileges, and benefits of this covenant, which are of two sorts:

- Of sanctifying, inherent grace; described by a double consequent:

- Of God’s relation unto them, and theirs to him; “I will be to them a God, and they shall be to me a people,” verse 10.

- Of their advantage thereby, without the use of such other aids as formerly they stood in need of, verse 11.

- Of relative grace, in the pardon of their sins, verse 12. And sundry things of great. weight will fall into consideration under these several heads.

- Of sanctifying, inherent grace; described by a double consequent:

Ver. 10. —For this is the covenant that I will make with the house of Israel after those days, saith the Lord; I will give my laws into their mind, and write them upon their hearts: and I will be unto them a God, and they shall be to me a people.

- The introduction of the declaration of the new covenant is by the particle o[ti. The Hebrew yKi, which is rendered by it, is variously used, and is sometimes redundant. In the prophet, some translate it by an exceptive, “sed;” some by an illative, “quoniam.” And in this place o[ti, is rendered by some quamobrem, “wherefore; and by others “nam,” or enim, as we do it by “for.” And it doth intimate a reason of what was spoken before, namely, that the covenant which God would now make should not be according unto that, like unto it, which was before made and broken.

- The thing promised is a “covenant:” in the prophet tyriB], here diaqh>kh. And the way of making it, in the prophet trOk]a,; which is the usual word whereby the making of a covenant is expressed. For signifying to “cut,” to “strike,” to “divide,” respect is had in it unto the sacrifices wherewith covenants were confirmed. Thence also were “foedus percutere,” and “foedus ferire.” See <011509>Genesis 15:9, 10, 18. Ta,, or μ[‘, that is, “cure,” which is joined in construction with it, Genesis 15:18, Deuteronomy 5:2. The apostle renders it by diaqhs> omai, and that with a dative case without a preposition, tw~| oi]kw,| “I will make” or “confirm unto.” He had used before suntele>sw to the same purpose. We render the words tyriB] and diaqh>kh in this place by a “covenant,’’ though afterward the same word is translated by a “testament.’’

A covenant properly is a compact or agreement on certain terms mutually stipulated by two or more parties. As promises are the foundation and rise of it, as it is between God and man, so it compriseth also precepts, or laws of obedience, which are prescribed unto man on his part to be observed. But in the description of the covenant here annexed, there is no mention of any condition on the part of man, of any terms of obedience prescribed unto him, but the whole consists in free, gratuitous promises, as we shall see in the explication of it. Some hence conclude that it is only one part of the covenant that is here described. Others observe from hence that the whole covenant of grace as a covenant is absolute, without any conditions on our part; which sense Estius on this place contends for. But these things must be further inquired into: —- The word tyriB], used by the prophet, doth not only signify a “covenant” or compact properly so called, but a free, gratuitous promise also. Yea, sometimes it is used for such a free purpose of God with respect unto other things, which in their own nature are incapable of being obliged by any moral condition. Such is God’s covenant with day and night, <243320>Jeremiah 33:20, 25. And so he says that he “made his covenant,” not to destroy the world by water any more, “with every living creature,” Genesis 9:10, 11. Nothing, therefore, can be argued for the necessity of conditions to belong unto this covenant from the name or term whereby it is expressed in the prophet. A covenant properly is sunqh>kh, but there is no word in the whole Hebrew language of that precise signification.

The making of this covenant is declared by yTir’K;. But yet neither doth this require a mutual stipulation, upon terms and conditions prescribed, unto an entrance into covenant. For it refers unto the sacrifices wherewith covenants were confirmed; and it is applied unto a mere gratuitous promise, Genesis15:18,“In that day did the LORD make a covenant with Abram, saying, Unto thy seed will I give this land.”

As unto the word diaqh>kh, it signifies a “covenant” improperly; properly it is a “testamentary disposition.” And this may be without any conditions on the part of them unto whom any thing is bequeathed.

- The whole of the covenant intended is expressed in the ensuing description of it. For if it were otherwise, it could not be proved from thence that this covenant was more excellent than the former, especially as to security that the covenant relation between God and the people should not be broken or disannulled. For this is the principal thing which the apostle designs to prove in this place; and the want of an observation thereof hath led many out of the way in their exposition of it. If, therefore, this be not an entire description of the covenant, there might yet be something reserved essentially belonging thereunto which might frustrate this end. For some such conditions might yet be required in it as we are not able to observe, or could have no security that we should abide in the observation of them: and thereon this covenant might be frustrated of its end, as well as the former; which is directly contrary unto God’s declaration of his design in it.

- It is evident that there can be no condition previously required, unto our entering into or participation of the benefits of this covenant, antecedent unto the making of it with us. For none think there are any such with respect unto its original constitution; nor can there be so in respect of its making with us, or our entering into it. For, —

- This would render the covenant inferior in a way of grace unto that which God made with the people at Horeb. For he declares that there was not any thing in them that moved him either to make that covenant, or to take them into it with himself. Everywhere he asserts this to be an act of his mere grace and favor. Yea, he frequently declares, that he took them into covenant, not only without respect unto any thing of good in them, but although they were evil and stubborn. See Deuteronomy 7:7,8, 9:4, 5.

- It is contrary unto the nature, ends, and express properties of this covenant. For there is nothing that can be thought or supposed to be such a condition, but it is comprehended in the promise of the covenant itself; for all that God requireth in us is proposed as that which himself will effect by virtue of this covenant.

- It is certain, that in the outward dispensation of the covenant, wherein the grace, mercy, and terms of it are proposed unto us, many things are required of us in order unto a participation of the benefits of it; for God hath ordained, that all the mercy and grace that is prepared in it shall be communicated unto us ordinarily in the use of outward means, wherewith a compliance is required of us in a way of duty. To this end hath he appointed all the ordinances of the gospel, the word and sacraments, with all those duties, public and private, which are needful to render them effectual unto us. For he will take us ordinarily into this covenant in and by the rational faculties of our natures, that he may be glorified in them and by them. Wherefore these things are required of us in order unto the participation of the benefits of this covenant. And if, therefore, any one will call our attendance unto such duties the condition of the covenant, it is not to be contended about, though properly it is not so. For, —

- God doth work the grace of the covenant, and communicate the mercy of it, antecedently unto all ability for the performance of any such duty; as it is with elect infants.

- Amongst those who are equally diligent in the performance of the duties intended he makes a discrimination, preferring one before another. “Many are called, but few are chosen;” and what hath any one that he hath not received?

- He actually takes some into the grace of the covenant whilst they are engaged in an opposition unto the outward dispensation of it. An example of this grace he gave in Paul.

- It is evident that the first grace of the covenant, or God’s putting his law in our hearts, can depend on no condition on our part. For whatever is antecedent thereunto, being only a work or act of corrupted nature, can be no condition whereon the dispensation of spiritual grace is superadded. And this is the great ground of them who absolutely deny the covenant of grace to be conditional; namely, that the first grace is absolutely promised, whereon and its exercise the whole of it doth depend.

- Unto a full and complete interest in all the promises of the covenant, faith on our part, from which evangelical repentance is inseparable, is required. But whereas these also are wrought in us by virtue of that promise and grace of the covenant which are absolute, it is a mere strife about words to contend whether they may be called conditions or no. Let it be granted on the one hand, that we cannot have an actual participation of the relative grace of this covenant in adoption and justification, without faith or believing; and on the other, that this faith is wrought in us, given unto us, bestowed upon us, by that grace of the covenant which depends on no condition in us as unto its discriminating administration, and I shall not concern myself what men will call it.

- Though there are no conditions properly so called of the whole grace of the covenant, yet there are conditions in the covenant, taking that term, in a large sense, for that which by the order of divine constitution precedeth some other things, and hath an influence into their existence; for God requireth many things of them whom he actually takes into covenant, and makes partakers of the promises and benefits of it. Of this nature is that whole obedience which is prescribed unto us in the gospel, in our walking before God in uprightness; and there being an order in the things that belong hereunto, some acts, duties, and parts of our gracious obedience, being appointed to be means of the further additional supplies of the grace and mercies of the covenant, they may be called conditions required of us in the covenant, as well as duties prescribed unto us.

- The benefits of the covenant are of two sorts:

- The grace and mercy which it doth collate.

- The future reward of glory which it doth promise.

Those of the former sort are all of them means appointed of God, which we are to use and improve unto the obtaining of the latter, and so may be called conditions required on our part. They are only collated on us, but conditions as used and improved by us.

- Although diaqh>kh, the word here used, may signify and be rightly rendered a “covenant,” in the same manner as tyriB] doth, yet that which is intended is properly a “testament,” or a “testamentary disposition” of good things. It is the will of God in and by Jesus Christ, his death and bloodshedding, to give freely unto us the whole inheritance of grace and glory. And under this notion the covenant hath no condition, nor are any such either expressed or intimated in this place.

- The word tyriB], used by the prophet, doth not only signify a “covenant” or compact properly so called, but a free, gratuitous promise also. Yea, sometimes it is used for such a free purpose of God with respect unto other things, which in their own nature are incapable of being obliged by any moral condition. Such is God’s covenant with day and night, <243320>Jeremiah 33:20, 25. And so he says that he “made his covenant,” not to destroy the world by water any more, “with every living creature,” Genesis 9:10, 11. Nothing, therefore, can be argued for the necessity of conditions to belong unto this covenant from the name or term whereby it is expressed in the prophet. A covenant properly is sunqh>kh, but there is no word in the whole Hebrew language of that precise signification.

Obs. I. The covenant of grace, as reduced into the form of a testament, confirmed by the blood of Christ, doth not depend on any condition or qualification in our persons, but on a free grant and donation of God; and so do all the good things prepared in it.

Obs. II. The precepts of the old covenant are turned all of them into promises under the new. —Their preceptive, commanding power is not taken away, but grace is promised for the performance of them. So the apostle having declared that the people brake the old covenant, adds that grace shall be supplied in the new for all the duties of obedience that are required of us.

Obs. III. All things in the new covenant being proposed unto us by the way of promise, it is faith alone whereby we may attain a participation of them. —For faith only is the grace we ought to exercise, the duty we ought to perform, to render the promises of God effectual to us, Hebrews 4:1,2.

Obs. IV. Sense of the loss of an interest in and participation of the benefits of the old covenant, is the best preparation for receiving the mercies of the new.

3. The author of this covenant is God himself: “I will make it, saith the\parLORD .” This is the third time that this expression, “Saith the Lord,” is repeated in this testimony. The work expressed, in both the parts of it, the disannulling of the old covenant and the establishment of the new, is such as calls for this solemn interposition of the authority, veracity, and grace of God. “I will do it, saith the Lord.” And the mention hereof is thus frequently inculcated, to beget a reverence in us of the work which he so emphatically assumes unto himself. And it teacheth us that, —

Obs. V. God himself, in and by his own sovereign wisdom, grace, goodness, all-sufficiency, and power, is to be considered as the only cause and author of the new covenant; or, the abolishing of the old covenant, with the introduction and establishment of the new, is an act of the mere sovereign wisdom, grace, and authority of God. It is his gracious disposal of us, and of his own grace; —that whereof we had no contrivance, nor indeed the least desire.

The Half-Way Covenant

Half-Way Covenant, religious-political solution adopted by 17th-century New England Congregationalists, also called Puritans, that allowed the children of baptized but unconverted church members to be baptized and thus become church members and have political rights. Early Congregationalists had become members of the church after they could report an experience of conversion. Their children were baptized as infants, but, before these children were admitted to full membership in the church and permitted to partake of the Lord’s Supper, they were expected to also give evidence of a conversion experience. Many never reported a conversion experience but, as adults, were considered church members because they had been baptized, although they were not admitted to the Lord’s Supper and were not allowed to vote or hold office.

Due to statements like the above, and because of the very name, I have always been under the impression that the position known as “the Half-Way Covenant” was invented by New England Congregationalists as a response to societal pressures. However, that is not really accurate. The following Wikipedia article is also representative of what I have previously read, but it is also quite inaccurate (notice the lack of citations):

The Half-Way Covenant was a form of partial church membership created by New England in 1662. It was promoted in particular by the Reverend Solomon Stoddard, who felt that the people of the English colonies were drifting away from their original religious purpose. First-generation settlers were beginning to die out, while their children and grandchildren often expressed less religious piety, and more desire for material wealth.

Full membership in the tax-supported Puritan church required an account of a conversion experience, and only persons in full membership could have their own children baptized.[citation needed] Second and third generations, and later immigrants, did not have the same conversion experiences. These individuals were thus not accepted as members despite leading otherwise pious and upright Christian lives.

In response, the Half-Way Covenant provided a partial church membership for the children and grandchildren of church members. Those who accepted the Covenant and agreed to follow the creed within the church could participate in the Lord’s supper. Crucially, the half-way covenant provided that the children of holders of the covenant could be baptized in the church. These partial members, however, couldn’t accept communion or vote.[1]

Puritan preachers hoped that this plan would maintain some of the church’s influence in society, and that these ‘half-way members’ would see the benefits of full membership, be exposed to teachings and piety which would lead to the “born again” experience,[citation needed] and eventually take the full oath of allegiance.[citation needed] Many of the more religious members of Puritan society rejected this plan as they felt it did not fully adhere to the church’s guidelines, and many of the target members opted to wait for a true conversion experience instead of taking what they viewed as a short cut.[who?]

Notice how this conflicts with the Brittanica article. Solomon Stoddard did not promote the Half-Way Covenant. He promoted an idiosyncratic position that admitted everyone to the Lord’s Supper as a converting ordinance, which is a different issue.

The Half-Way Covenant was specifically about baptism. New England Congregationalists, in forging the new path of Congregationalism, made a bold step in requiring a profession of saving faith (a demonstration of a work of grace in their lives) for membership. The reformed tradition only required profession of the true religion (“historical faith”). The question that arose was what to do with the children of people who had been baptized as infants into the church, but never made a profession of saving faith. Should these children be baptized?

When our churches were come to between twenty and thirty years of age, a numerous posterity was advanced so far into the world, that the first planters began apace in their several families to be distinguished by the name of grand-fathers ; but among the immediate parents of the grand children, there were multitudes of well disposed persons, who, partly thro’ their own doubts and fears, and partly thro’ other culpable neglect, had not actually come up to the covenanting state of covimunicants at the table of the Lord. The good old generation could not, without many uncom fortable apprehensions, behold their offspring excluded from the baptism of Christianity, and from the ecclesiastical inspection which is to accom pany that baptism; indeed, it was to leave their off-spring under the shepherdly government of our Lord Jesus Christ in his ordinances, that they had brought their lambs into this wilderness.

When the apostle bids churches to “look diligently, lest any man fail of the grace of God,” there is an ecclesiastical word used for that “looking diligently;” intimating that God will ordinarily bless a regular church-watch, to maintain the interests of grace among his people: and it was therefore the study”\ of those prudent men, who might he call’d our seers, that the children of \ ‘ the faithful may bo kept, as far as may be, under a church-watch, in i expectation that they might be in the fairer way to receive the grace of ! God; thus they were “looking diligently,” that the prosperous and pre vailing condition of religion in our churches might not be Res unius ailalis, — “a matter of one age alone.”

Moreover, among the next sons or daughters descending from that generation, there was a numerous appearance of sober persons, who professed themselves desirous to renew their baptismal-covenant and submit unto the church-discipline, and so have their houses also marked for the Lord’s; but yet they could not come up to that experimental account of their own regeneration, which would sufficiently embolden their access to the other sacraments. Wherefore, for our churches now to make no ecclesiastical difference between these hope ful candidates and competents for those our further mysteries, and Pagans, who might happen to hear the word of God in our assemblies, was judged a most unwarrantable strictness, which would quickly abandon the biggest part of our country unto heathenism. And, on the other side, it was feared that, if all such as had not yet exposed themselves by censurable scandals found upon them, should be admitted unto all the priviledges in our churches, a worldly part of mankind might, before we are aware, carry all things into such a course of proceeding, as would be very disagreeable unto the kingdom of heaven.

The magistrates of Connecticut and Massachusetts called for a synod to answer the issue. The synod’s answer was what has become known as the half-way covenant: the children of non-communicant members may be baptized. But the important point to understand was that the ministers did not see themselves as inventing or creating anything new. They were simply explaining and clarifying what had always been their position, and what had always been the reformed position. What was new was their requirement for a profession of saving faith in the first place.

What is interesting is the debate that ensued after the synod’s declaration. Increase Mather, son-in-law of John Cotton, objected to the report. He was born in New England and graduated from Harvard, but then studied in England and was a pastor there from 1658-1661. As a non-conformist he was forced to flee back to New England. It appears that this second generation of congregationalists did not share the reformed assumptions of their previous generation. Increase’s father Richard Mather was at the head of the synod’s report. The two were in disagreement, which was expressed via public written exchanges.

Increase could not understand, how someone who showed no signs of faith should be considered a Christian and thus should have their children baptized. His confusion stemmed from the new beliefs of the Congregationalist/Independent movement in New England. Separatists in England, in reaction to the Church of England, took steps towards a “pure church” concept by separating from the Church of England so they could administer their own discipline. Congregationalists, typically not Separatists (disavowing the Church of England), furthered this concept of the gathered church by requiring a profession of saving faith (conversion experience) prior to admitting a member to the Lord’s Supper (thus becoming a “communicant” member as opposed to a regular member). This has sometimes been referred to as a “church within a church”. (See Visible Saints: The History of a Puritan Idea)

This led to obvious conflict in Increase Mather’s understanding of membership. Eventually, he could not answer the logic flowing from the presuppositions regarding baptism itself and he humbly changed his mind, admitting that non-communicant members may have their children baptized.

The “Half-Way Covenant” was not an invention or a liberalizing tendency in New England churches. It was the historic reformed position. Rejection of this position is actually lamented by Presbyterian historians:

In view of the extensive acceptance of the Presbyterian theory of church order in the British Islands it is surprising that so long a period elapsed before it took root in any of the British colonies in America. Up to the time of Cromwell’s accession to power and even after that event the central and probably the largest body of the English Puritans were Presbyterians with moderate Episcopalians like Ussher and Reynolds forming the right wing while Independents and Baptists were the left. While the Pilgrim Fathers who settled the Plymouth colony were Independents on principle the Puritans of the Massachusetts Bay colony were largely Presbyterians in theory before their emigration. But the suppression of the attempts to set up the Genevan order in England in 1591 through the hostility of Archbishop Whitgift and its partial suspension in Scotland by the Compromise of 1586 and by the Articles of Perth in 1618 had prevented any practical application of Presbyterian principles within Great Britain. It was merely a theory and in the case of the English Puritans it was subject to the influence of that general tendency to pure individualism which dominated the whole Puritan movement From Anglican to Presbyterian from that to Independent and from that to Baptist ending often in Seekerism or Quakerism is the gamut through which the active spirits of the time easily ran.

In laying the foundations of church order in the absence of precedence and traditions and not uninfluenced by the proximity of the pronounced Independents of Plymouth the Puritans of New England drifted into arrangements which were midway between Presbyterianism and Independency with a strong leaning toward the latter. Not that there was no resistance to this. “The New England way,” as it was called, excited some sharp criticism among the Puritan divines in England and in 1637-39 there was a prolonged correspondence between them and their brethren on the subject, not entirely to their satisfaction. But the two tendencies struggled for the mastery for nearly seventy years, the Presbyterian finding able supporters in John Eliot (“The Divine Ordinance of Councils” 1665) and the Mathers.

Dr HM Dexter felicitously describes the New England way as a Congregationalized Presbyterianism which had its roots in one system and its branches in another and says that the Massachusetts churches differed locally from the almost Presbyterianism of Hingham and Newbury port to the pronounced Independency of Plymouth. But he is not so happy in his statement that the system was essentially Genevan within the local congregation and essentially other outside it. The absence of regularly constituted sessions for the administration of church discipline and the refusal of baptism to the children of baptized persons who were not communicants marked the local congregation as un Presbyterian. The latter rule was a rejection of the judgment of charity accepted by all the Reformed churches. It was one of the moot points between the two parties in the Westminster Assembly and in 1662 the severer rule had to be relaxed even in New England by the Half Way Covenant. On the other hand the high authority claimed and exercised by synods called by the civil magistrate of which six met during the seventeenth century shows that even outside the local congregation the New England way was not so entirely other than Genevan. We hear of no more such synods when the Congregational principle had attained supremacy in Massachusetts and the church order had taken the shape indicated in the writings of Rev John Wise (“The Churches Quarrell Espoused” 1710) who completed what John Cotton and his associates had begun.

Commenting on the above quote, Gordon Clark notes:

This emotional pietism, as it demanded a particular type of experience for regeneration, tended to view the ideal church as consisting entirely of regenerate persons sharing such an experience. The logical result is the Baptist position; but in Presbyterianism it stopped short at requiring the faith of the parents who wanted their children baptized. But if it did not result in Baptists practices, it involved a change in the theology of baptism.

-Sanctification, p. 65

(Side note: The Massachusetts synod insisted their principle only applied to the “next parent” and not to grandparents or ancestors, for “If we stop not at the next parent, but grant that ancestors may… convey membership unto children, then we should want a ground where to stop, and then all the children on earth should have right to membership and baptism.” To which Gordon Clark responded “Does the Bible require or prohibit baptisms to the thousandth generation? If it does, and if a generation is roughly thirty years, a thousand generation from the time of Christ would include just about everybody in the western world. Then the church should have baptized the child of an intensely Talmudic Jew whose ancestor in 50 B.C. was piously looking for the Messiah. Or, George Whitefield should have baptized Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, and Tom Paine, as children, because one of their ancestors played a small role in the Reformation. Strange as this may seem to many, it ought to have been done if the Bible so teaches.”)

All of that is just a very long winded way of saying that you should read Cotton Mather’s account of the debate, including the arguments from Increase Mather against the practice, and the response that he could not ultimately refute. It sheds great light on the question of baptism. You can read it in Volume II of Cotton Mathers’ Magnalia Christi Americana (p. 276), as well as Ch. 3 S. 6 of the Memoirs of Increase Mather (p. 17).

The Answer of the Elders and Other Messengers of the Churches, Assembled at Boston in the Year 1662, The Results of the Three Synods (Boston, 1725).

Quest. I. Who are the Subjects of Baptism?

The Answer may be given in the following Propositions, briefly confirmed from the Scriptures.

I. They that according to Scripture, are Members of the Visible Church, are the Subjects of Baptism.

2. The Members of the Visible Church according to Scripture, are visible Believers, in particular Churches, and their Infant i. e. Children in Minority, whose next Parents, one or both, are in Covenant.

3. The Infant-seed of Confederate visible Believers, are Members of the Church with their Parents, and when grown up, are personally under Watch, Discipline and Government of that Church.

4. These adult Persons, are not therefore to be admitted to full Communion, meerly because they are and continue Members, without such Qualifications, as the Word of God requireth thereunto.

5. Church-Members who were admitted in minority, understanding the Doctrine of Faith, and publickly professing their assent thereto; not scandalous in Life, and solemnly owning the Covenant before the Church, wherein they give up themselves and their Children to the Lord, and subject themselves to the Government of Christ in the Church, their Children are to be baptized.

6. Such Church-Members, who either by Death, or some other extraordinary Providence, have been inevitably hindred from publick acting as aforesaid, yet have given the Church cause in judgment of Charity, to look at them as so qualfied, and such, as had they been called thereunto, would have so acted; their Children are to be baptized.

7. The Members of Orthodox Churches, being sound in the Faith, and not scandalous in Life, and presenting due Testimony thereof; these occasionally coming from one Church to another, may have their Children baptized in the Church whither they come, by virtue of communion of Churches: But if they remove their Habitation, they ought orderly to covenant and subject themselves to the Government of Christ in the Church where they settle their abode, and so their Children to be baptized. It being the Churches duty to receive such unto Communion, so far as they are regularly fit for the same.

Here is a highlight of the ensuing debate:

Apology — VI. The application of the seal of baptism unto those who are not true believers, (we mean visibly, for De Occultis non Judical Ecclesia* The church passes no Judgment on the secrets of the heart) is a profanation thereof, and as dreadful a sin as if it man should administer the Lord’s Supper unto unworthy receivers; which is (as Calvin saith) as sacrilegious impiety, as if a man should take the blood or body of Christ and prostitute it unto dogs. We marvel that any should think that the blood of Christ is not as much profaned and villified by undue administration of baptism, as by undue administration of the Lord’s Supper.

In a private letter to Increase Mather, Mr. Mitchell summarized the debate:

“Please to consider which of these three propositions you would deny:

1, The whole visible church under the New Testament is to be baptized.

2, If a man be once in the church, nothing less than censurable evil can put him out.

3, If the parent be in the visible church, his infant child is so too.”

Increase could not answer the question.

Know, then, that Mr. Michael, partly by the light of truth fairly offered, and partly by the force of prayer for the good success of the offer, was too hard for the most learned apologist [Increase]; who, after he had written so exactly on the anti-synodalian side, that, finding that Scripture and reason lay most on the other side, not only surrendered himself a glad captive thereunto, but also obliged the church of God, by publishing unto the world a couple of most nervous treatises, in defence of the synodical propositions. The former of these treatises was entitled, ” The First Principles of New England, concerning the Subject of Baptism, and Communion of Churches:” wherein, because the anti- synodists commonly reproached the doctrine of the synod, as being no less hew than the practice of it, he answers this popular imputation of innovation and apostacy, by demonstrating, from the unquestionable writings of the chief and first fathers in our churches, that the doctrine of the synod was then generally believed by them: albeit the practice thereof had been buried in the circumstances of the “new plantation.”

Owen on Changing His Mind

He that can glory that in fourteen years he has not altered his conceptions of some things, shall not have me for his rival.

-Owen

Owen charged with inconsistency in his views

But Cawdry had more objects than one to accomplish by his work. It contained an Appendix shewing the inconstancy of the Doctor and the inconsistency of his former and present opinions. The proof of Owen’s inconstancy and inconsistency is that in 1643, being then connected with the Presbyterians, he published a Treatise in which he speaks on some points as a Presbyterian. In 1657 having been an Independent for at least ten years, as all the world knew, he published a book which contains sentiments bearing upon Independency. Ergo Owen is inconsistent and unstable. Alas for the logic of poor Daniel Cawdry. By such pitiful means do men sometimes endeavour to bring an opponent into disgrace.

Owen was not backward to reply. In the course of a few weeks he produced “A Review of the true nature of Schism with a Vindication of the Congregational Churches in England from the imputation thereof unjustly charged on them by Mr Daniel Cawdry” (Ox 1657 12mo pp 181 TM). He assures us in the Preface that it was the work of only four or five days which was all the time he could devote to it and all that he thought it deserved. With much firmness he meets and repels the charges of his adversary and strengthens his original position. He informs us That such was his unhappiness or rather happiness in the constant intercourse he had with Presbyterians both Scotch and English utterly of another frame of spirit that till he saw this treatise he did not believe that there had remained one godly person in England of such dispositions in reference to present differences. He shews successfully that Cawdry had completely failed in making out his charge of Schism and inconsistency against his brethren and himself and concludes the defence of his changes which we have fully narrated by simply remarking “He that can glory that in fourteen years he has not altered in his conceptions of some things shall not have me for his rival”

Abraham Booth’s “The Kingdom of Christ”

Here is a quote from the introduction to Abraham Booth’s The Kingdom of Christ. You can find more quotes/excerpts from this Evernote link.

This mistake of the Jews, respecting the kingdom of the Messiah, lying at the foundation of all the opposition with which they treated him, and of their own ruin; it behoves us to guard with diligence against every thing which tends to secularize the dominion of Christ : lest, by corrupting the Gospel Economy, we disho

nour the Lord Redeemer, and be finally punished as the enemies of his government. Our danger of contracting guilt, and of incurring divine resentment in this way, is far from being small. For we are so conversant with sensible objects, and so delighted with exterior show, that we are naturally inclined to wish for something in religion to gratify our carnality. Under the influence of that master prejudice, the expectation of a temporal kingdom, Jewish depravity rejected Christ; and our corruption, if we be not watchful, may so misrepresent his empire, and oppose his royal prerogatives, as implicitly to fay, ” We will not have him to reign over us.”*

* “As the great source of the infidelity of the Jews was a notion of the temporal kingdom of the Messiah, we may justly say, that the great source of the corruption of Christians, and of their general defection, foretold by the inspired writers, has been an attempt to render it, in effect, a temporal kingdom, and to support and extend it by earthly means. This is that spirit of Antichrist, which was so early at work, as to be discoverable in the days of the Apostles.” Dr. George Campbell’s Four Gospels Preface, p Iviu Second edition

John Erskine’s “The Nature of the Sinai Covenant”

Owen

Owen’s work on the Mosaic Covenant is tremendous. He was bold enough to recognize that the Old Covenant was separate from the Covenant of Grace (New Covenant), that it was made with the nation of Israel, that it was based upon works, and that it was limited to temporal life in the land (not eternal life).

However, when it comes to the question of what type of obedience was required, I think Owen can be improved upon. He noted:

This is the nature and substance of that covenant which God made with that people; a particular, temporary covenant it was, and not a mere dispensation of the covenant of grace.

That which remains for the declaration of the mind of the Holy Ghost in this whole matter, is to declare the differences that are between those two covenants, whence the one is said to be “better” than the other, and to be “built upon better promises.”

Those of the church of Rome do commonly place this difference in three things:

1. In the promises of them: which in the old covenant were temporal only; in the new, spiritual and heavenly.

2. In the precepts of them: which under the old, required only external obedience, designing the righteousness of the outward man; under the new, they are internal, respecting principally the inner man of the heart.

3. In their sacraments: for those under the old testament were only outwardly figurative; but those of the new are operative of grace.

But these things do not express much, if any thing at all, of what the Scripture placeth this difference in. And besides, as by some of them explained, they are not true, especially the two latter of them. For I cannot but somewhat admire how it came into the heart or mind of any man to think or say, that God ever gave a law or laws, precept or precepts, that should “respect the outward man only, and the regulation of external duties.” A thought of it is contrary unto all the essential properties of the nature of God, and meet only to ingenerate apprehensions of him unsuited unto all his glorious excellencies. The life and foundation of all the laws under the old testament was, “Thou shalt love the LORD thy God with all thy soul;” without which no outward obedience was ever accepted with him.

Hebrews 8 (p 105)

Pink

Perhaps the way in which Rome expressed or argued this point led Owen to reject it. But I think Owen was incorrect. Insofar as it was a national covenant, I believe it only required outward obedience. I think Pink is more correct on this point:

The covenant which God made with Israel at Sinai required outward obedience to the letter of the law… The Sinaitic covenant in no way interfered with the divine administration of either the everlasting covenant of grace (toward the elect) nor the Adamic covenant of works (which all by nature lie under); it being in quite another region. Whether the individual Israelites were heirs of blessing under the former, or under the curse of the latter, in no wise hindered or affected Israel’s being as a people under this national regime, which respected not inward and eternal blessings, but only outward and temporal interests.

In his “Divine Covenants”, A.W. Pink quotes Abraham Booth at length to establish this critical point:

“It is of great importance to the right interpretation of many passages in the O.T., that this particular be well understood and kept in view. Jehovah is very frequently represented as the Lord and God of all the ancient Israelites; even where it is manifest that the generality of them were considered as destitute of internal piety, and many of them as enormously wicked. How, then, could He be called their Lord and their God, in distinction from His relation to Gentiles (whose Creator, Benefactor, and Sovereign He was), except on the ground of the Sinai covenant? He was their Lord as being their Sovereign, whom, by a federal transaction they were bound to obey, in opposition to every political monarch who should at any time presume to govern them by laws of his own. He was their God, as the only Object of holy worship; and whom, by the same National covenant, they had solemnly engaged to serve according to His own rule, in opposition to every Pagan idol.

…Again, as none but real Christians are the subjects of our Lord’s kingdom, neither adults nor infants can be members of the Gospel Church in virtue of an external covenant or a relative holiness. A striking disparity this, between the Jewish and the Christian Church. A barely relative sanctity [that is, a sanctity accruing from belonging to the nation of God’s choice, A.W.P.] supposes its possessors to be the people of God in a merely external sense; such an external people supposes an external covenant, or one that relates to exterior conduct and temporal blessings; and an external covenant supposes an external king.

…The covenant made at Sinai having long been obsolete, all its peculiarities are vanished away: among which, relative sanctity [that is, being accounted externally holy, because belonging to the nation separated unto God, A.W.P.] made a conspicuous figure. That National Constitution being abolished, Jehovah’s political sovereignty is at an end.

The Covenant which is now in force, and the royal relation of our Lord to the Church, are entirely spiritual. All that external holiness of persons, of places, and of things, which existed under the old economy, is gone for ever; so that if the professors of Christianity do not possess a real, internal sanctity, they have none at all. The National confederation at Sinai is expressly contrasted in Holy Scripture with the new covenant (see Jer. 31:31-34; Heb. 8:7-13), and though the latter manifestly provides for internal holiness, respecting all the covenantees, yet it says not a word about relative sanctity” (Abraham Booth, 1796).

Pink, Arthur W. (2010-03-19). The Divine Covenants (Kindle Locations 2607-2635). . Kindle Edition.

Booth

If you consult Abraham Booth’s The Kingdom of Christ on this point, he further references someone else:

Performing the conditions of their National Confederation, they were, as a people, warranted to expect every species of temporal prosperity. Health and long life, riches, honours, and vic tory over their enemies, were promised by Jehovah to their external obedience. (Ex 25:25,26; 28:25-28; Lev 26:3-14; Deut 7:12-24; 8:7-9; 11:13-17; 28:3-13) The punishments also, that were denounced against flagrant breaches of the Covenant made at Horeb, were of a temporal kind.*

*Lev. xxvi. 14—39. Deut. iv. 25, 26, 27* xi. 9.7. xxviii. 15— 68. xxix. 22— 28, See Dr. Erskine’s Theological Dissert. p. 22– 29. External obedience. — Punishments of a temporal kind. These and similar expressions in this essay are to be underwood, as referring to the Sinai Covenant strictly considered, and to Jehovah’s requisitions as the king of Israel. They are quite consistent, therefore, with its being the duty of Abraham’s natural seed to perform internal obedience to that sublime Sovereign, considered as the God of the whole earth; and with everlasting punishment being inflicted by him, as the righteous desert of sin.

Erskine

John Erskine was a contemporary of Booth (1721–1803). He was a Scottish Presbyterian. “Unusual for minister at that time, the highborn Erskine purposely chose the office of the pastorate for his profession, knowing that one day he would inherit his father’s and grandfather’s estates at Carnock and Torryburn. Erskine’s family assumed he would follow his father’s footsteps and become a lawyer, but Erskine had different plans for his life. Impassioned to contribute to the growth of the evangelical revival in Britain and America, Erskine believed that as a minister he would have the best opportunity to lend a hand to this worthy Christian enterprise.” (Yeager)

John Erskine was a contemporary of Booth (1721–1803). He was a Scottish Presbyterian. “Unusual for minister at that time, the highborn Erskine purposely chose the office of the pastorate for his profession, knowing that one day he would inherit his father’s and grandfather’s estates at Carnock and Torryburn. Erskine’s family assumed he would follow his father’s footsteps and become a lawyer, but Erskine had different plans for his life. Impassioned to contribute to the growth of the evangelical revival in Britain and America, Erskine believed that as a minister he would have the best opportunity to lend a hand to this worthy Christian enterprise.” (Yeager)

He defended the rights of the American colonies against the British, was a vocal member of the Slave Abolition Society, and led the evangelical party of the Church of Scotland in a passionate plea for the work of missions. In short, he was not afraid to speak his mind in controversial matters. His “Dissertation I: The Nature of the Sinai Covenant, and the Character and Privileges of the Jewish Church“, intended to be read along with “Dissertation II: The Character and Privileges of the Apostolic Churches” as an argument against the national church, noting “The greater part of modern Christians, have, I acknowledge, in their sentiments of the nature of the church, widely deviated from Scripture and antiquity. And the fiction of a visible church, really in covenant with God, and yet partly made up of hypocrites, has almost universally prevailed.”

The thrust of his argument was to demonstrate that the Old Covenant is separate from the New Covenant and thus cannot be a model for the Christian Church.

The common distinction of the church into visible and invisible, or at least the incautious manner in which some have explained it, has contributed not a little to the prevalence of this opinion. But let us impartially examine, whether it has any solid foundation in the sacred oracles; and for this purpose enquire whether the proofs of such an external covenant under the Old Testament, will equally apply to gospel times.

To prove this, Erskine labored to explain that the Sinai Covenant was established with God as a “temporal prince”. Thus it required outward, temporal obedience to the monarch of the land of Canaan.

That God was one of the parties, in the Mosaic covenant, is universally acknowledged. It is, however, necessary to observe, that God entered into that covenant, under the character of King of Israel. He is termed so in Scripture (Judges 8:23, 1 Sam 8:7, 12:12) and he acted as such, disposed of offices, made war and peace, exacted tribute, enacted laws, punished with death such of that people as resufed him allegiance and defended his subjects from their enemies…

he appeared chiefly as a temporal prince, and therefore gave laws intended rather to direct the outward conduct, than to regulate the actings of the heart. Hence every thing in that dispensation was adapted to strike his subjects with awe and reverence. The magnificence of his palace, and all its utensils ; his numerous train of attendants ; the splendid robes of the high priest, who, though his prime minister, was not allowed to enter the holy of holies, save once a year, and, in all his ministrations, was obliged to discover the most humble veneration for Israel’s king ; the solemn rites, with which the priests were consecrated ; the strictness with which all impurities and indecencies were forbidden, as things, which, though tolerable in others (Deut 14:21), were unbecoming the dignity of the people of God…

To conclude this argument, the fidelity and allegiance of the Jews was secured, not by bestowing the influences of the spirit necessary to produce faith and love, (Deut 29:3-4) but barely by external displays of majesty and greatness, calculated to promote a slavish subjection, rather than a chearful filial obedience. (p. 4-6)

Because this was an earthly kingdom, the unregenerate were included in the covenant.

The party, with whom God made this covenant, was the Jewish nation, not excluding these unregenerate, and inwardly disaffected to God and goodness. In the original records of the Sinai covenant (Ex 19:8, 24:3, Deut v:1-3), all the people are expressly said to enter into it, and yet the greater part of that people, were strangers to the enlightening and converting influences of the spirit, and to a principle of inward love to God and holiness (Deut 29:3, 5:29).

…Descent from Israel gave any one a title to the benefits of this covenant, for which reason the children even of unregenerate Israelites, were circumcised the eighth day, and were said to be born unto God (b).

…Hence Paul tells us, that he had, whereof be might trust in the flesh, he esteemed himself entitled to the carnal benefits of the Sinai covenant, seeing he was of the flock of Israel’, and an Hebrew of the Hebrews (d). Now this plainly supposes, that all of the flock of Israel were interested in that covenant. Nay, these adopted by a Jew, born in his house, or bought with his money, were circumcised, as a token that they were entitled to the same benefits (e).

{a) Deut. xxix. 14, 15. (b) Ezek.xvi. 20. (c) Mat. iii. 9. John viii. 33. (d) Phil. iii. 4, 5. (e) Gen. xv)i. 12, 13. Seidell de Jur. Nat. & Gent. 1. 5. c. n.

The blessings of the covenant were temporal.

[T]he blessings of the Sinai covenant are merely temporal and outward. God in that covenant acted as a temporal monarch. And from a temporal monarch, temporal profperity is all that we hope, not spiritual bleffings, such as righteousness, peace and joy in the Holy Ghost.

…[P]romises of temporal blessings and threatenings of the opposite evils are almost every where to be found in the Scripture accounts of the Sinai covenant, whilst there is a remarkable silence as to spiritual and heavenly blessings. (28)

Erskine believed that the Sinai Covenant was of works. “All these promises may be considered as so many enlargements, or rather explications of that general one, Lev 18:5 ‘The man that doeth these things shall live in them’” (28). He said “the Mosaic covenant had a respect to the covenant of grace as typified by it. But then the burdensome servile obedience it enjoined, was to be performed by the Jews without any special divine assistance, and was to found their legal title to covenant blessings.”

It is now time to investigate the condition, the performance of which entitled to the blessings of the Sinai covenant. …in general, obedience to the letter of the law, even when it did not flow from a principle of faith and love. A temporal monarch claims from his subjects, only outward honour and obedience. God therefore, acting in the Sinai covenant, as King of the Jews, demanded from them no more. (37)

This understanding sheds light on many passages of Scripture.

He who yielded an external obedience to the law of Moses, was termed righteous, and had a claim in virtue of this his obedience to the land of Canaan, so that doing these things he lived by them (s). Hence, says Moses (t), “It shall be our righteousness, if we observe to do all these commandments,” i. e. it shall be the cause and matter of our justification, it shall found our title to covenant blessings. (44)

(s) Lev. xviii. 5. Deut. v. 33. (t) Deut. vi.25

…Deut 26:12-15 – Would God have directed them, think you, to glory in their observance of that law, if, in fact, the sincerest among them had not observed it. Yet doubtless that was the case, if its demands were the same as those of the law of nature. But indeed, the things mentioned in that form of glorying were only external performances, and one may see, with half an eye, many might truly boast they had done them all, who were strangers not with-standing to charity, flowing from a pure heart, a good conscience, and faith unfeigned. Job, who probably represents the Jews after their return from the Babylonish captivity, was perfect and upright {v). Zacharias and Elizabeth were both righteous before God, walking in all the commandments and ordinances of the Lord blameless(w). The young man, who came to Jesus, enquiring what he should do to inherit eternal life, professed that he had kept the commandments from his youth up, and our Lord does not charge him with falsehood in that profession (x). Paul was touching the righteousness which was of the law, blameless (y). Yet Job curses the day in which he was born (z) Zacharias is guilty of unbelief {a) ; the young man, in the gospel loves this world better than Christ (b) ; and Paul himself groans to be delivered from a body of sin and death (c), These seeming contradictions will vanish, if we take notice, that all of these though chargeable with manifold breaches of the law of nature, had kept the letter of the Mosaic law, and thus were entitled to the earthly happiness promised to its observers.

(v) Job i. i» xix. 20. (a) Luke i. ao. vii. 24.

Luke i. 6. (x) Matth. (y) Phil. iii. 6. (z) Job iii. i, 3. (Jb) Mat. xix, 22, 23. (c) Rom.

Bishop Warburton has observed, Divine Legation vol. II. part I. p. 355,—360. that the title of Man after God’s own heart, was given to David, not on account of his private morals, but of a behavior so different from that of Saul, in steadily maintaining purity of worship. (47)

Erskine’s ultimate goal was to demonstrate the glory of the gospel age.

The blessings of the Sinai covenant, were patterns of the heavenly things (Heb 9:9,23), shadows of good things to come (Col 2:16,17), and surely patterns and shadows differ in nature from the things of which they are patterns and shadows. (33)

Israel’s deliverance from Egypt, which was as it were the foundation of the Sinai covenant, was only an outward redemption. Is it then reasonable to suppose, that the blessings founded upon it were spiritual and heavenly? (24)

Obedience to them [Mosaic laws] was never designed to entitle to heavenly and spiritual blessings. These last are only to be looked for through another and a better covenant, established upon better promises. (4)

The Israelites were put upon obedience as that which would found their claim to the blessings of the Sinai covenant. But they were never put upon seeking eternal life by a covenant of works. It is on this account, that the Mosaic precepts are termed, Heb. ix. 10, carnal ordinances, or, as it might be rendered, righteousnesses of the flesh, because by them men obtained a legal outward righteousness… But to Spiritual and heavenly blessings, we are entitled only by the obedience of the son of God, not by our own. (44)

…The difference of the Christian dispensation from the Sinai covenant, in these respects, is hinted, John i. 13. and 1 Peter i. 23. and in that celebrated expression of Tertullian, “Christiani fiunt, non nafcuntur. It needs no proof, that men might be interested in the blessings of the Sinai covenant, in any of the ways mentioned above, and yet notwithstanding be slaves of Satan, and dead in trespasses and sins. When God promised the land of Canaan to Abraham and his seed, circumcision was instituted for this among other purposes, to shew that descent from Abraham was the foundation of his posterities right to these blessings. But, in gospel times, when not the children of the flesh, but the children of the promise are counted for a seed, Rom. ix. 8. in consequence of this the circumcision of the flesh is of no more avail, and the circumcision made without hands, in putting off the body of the sins of the flesh by the circumcision of Christ becomes necessary, Col. ii. ir. Rom. ii. 28. (9)

…Agreeably to all this, we are told Heb. ii. 3. that ” the great salvation first began to be “preached by the Lord” 2 Tim. i. 9, 10. that the gracious purpose of God for the salvation of sinners is only “now made manifest by the appearing of our Saviour Jesus Christ, who hath “brought life and immortality to light thro the “gospel” and Heb. ix. 8. that “the way into” the holiest of all was not yet made manifest, “while as the first tabernacle was yet standing.”

If Jesus was the first who plainly published the doclrine of salvation; if, until he appeared, the purposes of redeeming love were not opened and unfolded, and immortal life was not brought to light ; if the Jewish dispensation did not declare the means of obtaining the heavenly happiness we muft conclude, that there were not in the Sinai covenant, promises of spiritual and eternal blessings. But why need I multiply arguments, when the authority of two divinely inspired writers has been interposed, to decide the controversy. We are not only told Jer. xxxi. 31,—34. and Heb. viii. 12. that the Sinai and gospel covenants were essentially different: but are also informed, in what that difference chiefly consisted, even that the latter conferred pardon of sin and the enlightening and sanctifying influences of the spirit. Now this could be neither instance nor proof of such a difference, if the Sinai covenant had done the same things. But the words of the author to the Hebrews will bid fairer to strike conviction into the candid reader, than any thing I can say in illustration of them. (35)

Of course, this raised an immediate objection (as it does today): Are you saying Israelites weren’t saved?

Let it not however be thought, I would conclude from this and such like Scriptures, that none under the Sinai covenant had an interest in spiritual blessings. I only mean to alert, that the claim of the inwardly pious Jew to pardoning mercy, to sanctifying grace, and to the heavenly glory, was no more founded on his obedience to Moses’s law, than Job’s claim to these bleflings was founded on his being born in the land of Uz, and having seven sons and three daughters. The special favor of God was vouchsafed both to Jew and Arabian, only in virtue of that promise, which being before the law, could not be annulled by it (Gal 3:17). The law, or Sinai covenant, made nothing perfect, that honour being referved to the bringing in of a better hope (Heb 7:19). It could not give life (Gal 3:21). It could not give righteousness (2 Cor 3:9). Sins committed under it, as to their moral guilt, and spiritual and eternal punifhment, were forgiven only in consequence of the New Teftament, confirmed by the death of Chrift (Heb 9:15), without whose death the righteousness of God in forgiving these sins could not have been manifested (Rom 3:25). So that without us, the Old Testament saints were not made perfect (Heb 11:40) (36-37)

…The dispensation of grace, which took place under the Mosaic covenant, was no part of it, did not extend to all who were, and did extend to some who were not under it. (3)

Yet many will still object that there were very clearly revelations of spiritual things in the Old Testament. How can this be reconciled with what has been argued?

You will ask, if this reasoning is just, why did the prophets so often insist upon it, that Sacrifices and meer outward obedience were not acceptable to God (d)? I answer, in many such passages, the Jews are rebuked for neglecting the moral law, and placing all their religion in the ceremonial. (48)

(d) Pfal. 1. 8. Ila. i. 11. xliii. 13. Jer. vii. si. Hof. v. ,6, 7. vi. 6. Mic. vi. 8.

…We must not imagine that everything in Moses’s writings relates to the Sinai covenant. Some things in them were intended as a republication of the law of nature. And they contain many passages, which evidently relate to the duties and privileges of thofe interested in the gospel covenant. (49)

…I would further observe, that the laws of Moses in general had a Spiritual and a literal meaning The righteousness upon which the temporal prosperity of Israel depended, was the righteousness of the letter of the law. The righteousness through which believers are entitled to eternal life, is the righteousness of the spirit of the law. And as the earthly Canaan was a type of heaven, so that external obedience which gave a right to it, prefigured that perfect obedience of the Redeemer, whereby alone we are entitled to the heavenly bliss. The law therefore, in its spiritual sense, required inward, nay, even perfect obedience. And possibly the prohibition of coveting, and the precept of loving God with all the heart, were left in the letter of the law, to lead good men to the spirit of it : the very letter of these precepts, when taken in their full emphasis, reaching to the inmost thoughts and intents of the heart, and forbidding the least sinful desire.

This explains in what sense Paul asserts (Rom 7:8-11), that in taking occasion by the commandment, wrought in him all manner of concupiscence, yea, deceived him and slew him. Perceiving as an ingenious congregational minister well remarks (Glass’ Notes on Scripture texts No. 2 p. 28, 29), that the precept thou shalt not covet, commanded not only his outward conversation, but had a spiritual sense in which it reached the very thoughts and affections of the heart : while he was yet in the flesh, he set himself with all his might to obey this precept, bound himself with vows and resolutions against the breach of it, and earnestly implored the divine assistance to render his endeavours effectual, that so he might be blameless in the righteousness of the law. But the more he set his heart on this righteousness, he would be the more strongly affected to the earthly happiness annexed to it as its reward : and thus all his attempts to be righteous by not coveting, only served to quicken and inflame his covetousness. So that finding himself utterly incapable to keep this command, he saw his sin exceedingly sinful, and found himself condemned to death, by the spiritual sense of that very law, by which he once thought to live.Yet still the breach of these precepts, in this their full emphasis and spiritual meaning, was no breach of the Sinai covenant : since, as has been already urged, heart sins were neither punished by death, nor expiated by sacrifice

…These remarks will serve to illustrate, what is meant by the flesh and by the spirit in Paul’s epistles to the Romans and Galatians. Mr. Glass has observed (Glass’ Notes, No. 3, p. 27 and 5), that the letter of the law, or the law in that carnal view without the spirit of it in which it is set before us, Rom. vii. i, 5, 6. the state of the nation under it, and the suitable disposition of that people to perform the national righteousness, and to enjoy the national happiness annexed to it as its reward, is called the flesh. In some Scriptures the flesh means bondage under the Sinai covenant (v) ; and the condition of that covenant is described as the law of a carnal commandment (w), and as consisting in carnal ordinances (x). The rewards also of that covenant were carnal, and so was the disposition of the Jewish people. Meat and drink were in their esteem chief blessings of the kingdom of God (y). Their god was their belly (z). And hence of old they gathered themselves for corn and wine (a), and afterwards sought the Saviour, not because they saw his miracles, but because they did eat of the loaves and were filled (b). These then are not after the flesh, but after the spirit, whose prevailing desire it is, not to establish their own righteousness, and to enjoy an earthly happiness, but to be clothed with a Redeemer’s righteousness, and through him to attain the blessings of a spiritual and divine life. (t) Exod. xxxiv. 24. (v) Isa. xl. 6. Phil. iii. 3. Gal.

Heb. vii. 16. (x) Heb. ix. 10. (y) Rom. xiv. 17 (z) Phil iii. 3. (a) Hos vii. 14, (b) Jo. vi 26

(51)

This had clear implications for the doctrine of justification in Erskine’s day just as it does for us today.

The preceding pages will guide to the meaning of several texts, which have been often urged for the unscriptural tenets of justification by the deeds of the law, and of the attainableness of perfection in a present life. I shall not trespass on the patience of my readers, by spending time in illustrating what is so obvious.

…Ezek. xviii. 24, 26. has been often appealed to as an evidence, that faints may fall from grace, and eternally perish. The fallacy of this argument will appear, if we take notice, that a righteous man here means one, who yields an external obedience to the law of Moses, and in virtue of that obedience has a righteous title (Deut 6:25) to long life and prosperity in the land of Canaan.

…Of such a one it is said, Ezk 28 ver. 22. “in his righteousness that he hath done, he shall live.” i. e. he shall receive life on account of his good works : whereas persons just, in an evangelical sense, are entitled to eternal life by the righteousness of the Redeemer, and live by faith. (56)

One other important objection Erskine answers is how could God establish a covenant based upon works with people already condemned in Adam?

But, if this reasoning proves anything, will it not prove, that a God of spotless purity, can enter into a friendly treaty with men, whom yet, on account of their sins, he utterly abhors. And what if it does? Perhaps, the assertion, however shocking at first view, may, on a narrower scrutiny, be found innocent. We assert not any inward eternal friendship between God and the unconverted Jews. We only assert an external temporal covenant, which, though it secured their outward prosperity, gave them no claim to God’s special favour. Where then is the alleged absurdity? Will you say it is unworthy of God to maintain external communion with sinners, or to impart to them any blessings? What then would become of the bulk of mankind? Nay, what would become of the patience and longsuffering of God? Or is it absurd, that God should reward actions that flow from bad motives when we have an undoubted instance of his doing this in the case pf Jehu? Or is it absurd, that God would entail favours on bad men, in the way of promise or covenant? Have you forgot God’s promise to Jehu, that his children of the fourth generation should sit on the throne of Israel? Or have you forgot, what concerns you more, God’s covenant with mankind in general, no more to deftroy the earth by a flood (2 Kings 10:30; Gen 9:12)? (15-16)

I was blessed by Erskine’s work because it really helped me understand just how glorious the revelation of the New Covenant is compared to the darkness of the Old Covenant. Yes, we can look back now and clearly see Christ in all sorts of ways. But it was not so obvious to the majority of Israelites under the Sinai covenant. In light of the above, ponder 1 Samuel 11:13 closely and ask yourself if it’s any real surprise the Jews expected Christ to deliver them from the Romans.

That Christ, and the benefits of Redemption, were typified by the Law of Moses and that the spiritual sense of Moses’ Law, though veiled from the Jews in common was in some measure revealed to those mentioned, Heb. xi. I firmly believe. I doubt not, there were many more, whose eyes were opened, under that dark dispensation, to behold wonderous things out of God’s Law. (vii)

Perhaps it may be alledged to invalidate my argument, that the land of Canaan was a type of the heavenly inheritance: that the temporal blessings of the Sinai covenant, were representations, earnests, and pledges of spiritual and eternal blessings : that the meaning of these types and figures was explained to those to whom “they were first delivered, and by oral tradition transmitted to succeeding ages : so that the Sinai covenant was enforced not only by the temporal promises which it literally contained., but also by the spiritual promises which the letter of that covenant pointed out.—As this is plausible, it merits to be thoroughly examined.That types not explained, were too obscure a medium, for conveying the pretended spiritual sanctions of the Sinai covenant, especially to so gross and carnal a people as the Jews, will be proved § 5. Now no explanation is given of the types, in the books of the Old Testament, which were the only rule of faith and practice to the Jewish church. And finely, that which was intended as a principal sanction of the Sinai covenant, would not have been left to so treacherous and uncertain a method of transmission as oral tradition. We are told, 2 Cor. iii. 13. that ” Moses put a veil over his face, that the children of Israel could not steadfastly look to the end of that which is abolished,” i. e. could not discern what was typified by the precepts and sanctions of the temporary Sinai covenant. Surely, casting a veil over an object, and holding it up to full and open view, are two things so very opposite, that a scheme to do both at once, could never enter into any rational mind. If the meaning of the types was delivered to the Jewish church, a typical delineation would no more have veiled from them the spirit of the law, than the meaning of a Greek or Latin classic is veiled from a boy at school, by publishing it along with an exact literal translation into his mother language. The nature of types demonstrates, that they can have no existence, where there is nothing to be veiled or covered. If therefore, when the law of Moses was given to Israel, the spiritual sense of it was known, or was intended to be revealed, a carnal veil to conceal that sense, must on either of these suppositions be absurd and preposterous. So that the typical genius of the Old Testament, instead of proving, plainly confutes the alleged spiritual sanctions of the Sinai covenant.

…And it seems to me less culpable to adopt sentiments, which I could not improve than to do wrong to my argument by omitting an essential branch of it, and perhaps also to raise suspicions in some of my readers, that I declined meddling with a knotty objection, merely becaufe I was conscious I could not resolve it. Upon the whole, I firmly believe that Canaan was a type of the heavenly inheritance. But this only proves, that it represented heaven, as the Jews who possessed it, represented the heirs of heaven. It does not prove, that the land flowing with milk and honey, was bestowed, to reveal and seal to its inhabitants spiritual and heavenly blessings. (29-32)

1 Cor 5:13 is the general equity of Deut 22:21 (TRL)

1 Cor 5:13 is the general equity of Deut 22:21 @ The Reformed Libertarian (sorry, original link was wrong – its working now)

Would love to hear your thoughts

The More Things Change…

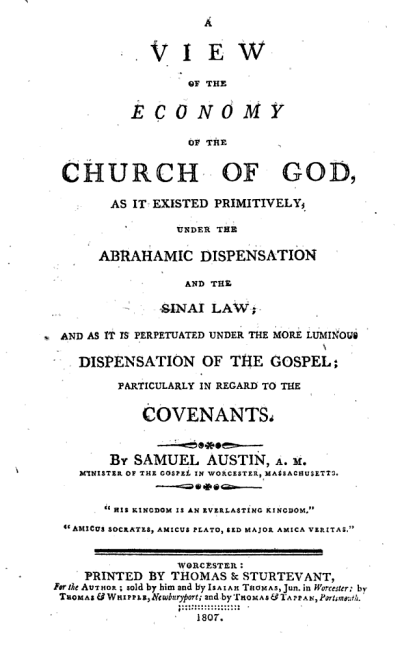

I was trying to dig up a reference and came across this intro to a book from 1807:

INTRODUCTION.

SEVERAL works have been published within a few. years, both in Europe, and in this Country, concerning tie Church of God; particularly, the qualifications which are requisite for membership in it, its institutions, the persons to to whom they ought to be extended, and the discipline which its officers, and ordinary members are to maintain in it- The Baptist controversy, in which all these subjects are more or less involved, has been lately revived- Books are multiplied, without bringing this controversy to a close. Difficulties still remain, to perplex the humble enquirer, and keep up the vehemence of debate. Much truth is exhibited. But a clear, consistent scheme, disembarrassed of real difficulties, seems to be wanting. Such a scheme the Bible undoubtedly contains. To elicit this scheme is the only way, to bring honest minds to an agreement. Whoever will candidly review the most ingenious Treatises which have been published in the Baptist controversy, will perceive that the Pcedobaptists have a great pre ponderance of evidence on their side of the question. It will, at the same time, be perceived, that they are not as united as could be wished in the principles of their theory. Some rest the evidence that the infant seed oj believers are proper subjects of baptism, almost wholly upon the covenant which God established with Abraham. Others have not so much re spect to this kind of argument ; but prefer to rest the defence of their opinion, and practice, upon what they apprehend to be the clearer intimations of the Gospel, and upon the re cords oj history. Different views are entertained of the nature of the Abrahamic covenant: It is debated whether this covenant was strictly, and properly the covenant of Grace ; what was the real import, and who were the objects of its promises. Different opinions are entertained, and contrary hypotheses advocated also, respecting the Sinai covenant, the dispensation by Moses generally, and the constitution and character of the community of Israel. Some very respected and learned divines among the Pcedobaptists have adopt ed the idea, that this community was of a mixed character, and have called it a Theocracy. Among the many advocates of this opinion are Lozvman, Doddridge, Warburton, Guise, and the late John Erfkine. These Divines supposed, that the legation of Moses could be best defended against the ca vils of unbelievers, by placing God at the head of the community of Israel, as a civil governor , surrounding himself with the regalia, and managing his subjects with the penalties and largesses, of a temporal sovereign.