[This essay is available as a PDF, ePub, or Kindle]

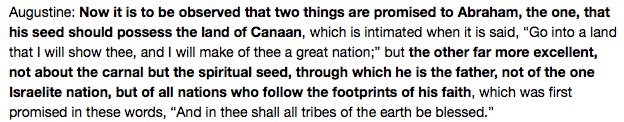

Augustine

In a helpful essay titled “The Covenant in the Church Fathers”, Andrew A. Woolsey notes that “Augustine built upon the patristic position, with his main emphasis upon two covenants, the ‘old’ as manifested supremely in the Sinaitic arrangement, and the ‘new’ in Christ.” with the important qualification that “Augustine did not confine the giving of the law covenant to Sinai… he considered the Sinaitic covenant to be ‘a more explicit’ form of a pre lassos Edenic covenant made with Adam.”[1] The difference between the Adamic and the Old Covenants was that “obedience to the [Edenic] covenant, Augustine speculated, would have caused Adam to pass into the company of the angels with no intervening death, to ‘a blissful immortality that has no limit’”[2] while the Old was limited to temporal blessings in Canaan. “[T]he law of works, which was written on the tables of stone, and its reward, the land of promise, which the house of the carnal Israel after their liberation from Egypt received, belonged to the old testament [covenant]… the promises of the Old Testament are earthly… In that testament, however, which is properly called the Old, and was given on Mount Sinai, only earthly happiness is expressly promised.”[3]

Salvation is found in Christ the mediator through the New Covenant, which was “hidden in the prophetic shadows until the time should come wherein it should be revealed in Christ.”[4] “These pertain to the new testament [covenant], are the children of promise, and are regenerated by God the Father and a free mother. Of this kind were all the righteous men of old, and Moses himself, the minister of the old testament, the heir of the new,—because of the faith whereby we live, of one and the same they lived, believing the incarnation, passion, and resurrection of Christ as future, which we believe as already accomplished.”[5] “Now all these predestinated, called, justified, glorified ones, shall know God by the grace of the new testament [covenant], from the least to the greatest of them.”[6]

Woolsey explains that “Christ was their Mediator too. Though his incarnation had not yet happened, the fruits of it still availed for the fathers. Christ was their head… So the men of God in the Old Testament were shown to be heirs of the new. The new covenant was actually more ancient than the old, though it was subsequently revealed. It was ‘hidden in the prophetic ciphers’ until the time of revelation in Christ.”[7]

Augustine developed his covenant theology amidst debate with Pelagians, who denied total depravity and taught that man may be righteous through obedience to the law and that many in the Old Testament were. One of five formal charges brought against Pelagius was his claim that “The Law leads people to the kingdom of heaven in the same way as does the gospel.”[8] Pelagius argued that “The kingdom of heaven was promised even in the Old Testament.” Augustine’s response was that the Old Testament Scriptures do reveal the kingdom of heaven, but in the Old Covenant “given on Mount Sinai, only earthly happiness is expressly promised.” However, it served as “figures of the spiritual blessings which appertain to the New Testament.” Saints during that time who understood this distinction “were accounted in the secret purpose of God as heirs of the New Testament.”[9] Eugen J. Pentuic explains “In chapters 14 and 15 [of On the Proceedings of Pelagius], Augustine seeks to refute Pelagius’s thesis on the parity between the Law and the gospel. For Augustine, the distinction between the two testaments lies with the nature of their promises. If the Old Testament’s promises are centered on earthly realities, the New Testament’s promises concern the heavenly realities such as the kingdom of heaven.”[10]

Augustine argued that “by the words of Pelagius the distinction which has been drawn by Apostolic and catholic authority is abolished, and Agar is supposed to be by some means on a par with Sarah[.] He therefore does injury to the scripture of the Old Testament with heretical impiety, who with an impious and sacrilegious face denies that it was inspired by the good, supreme, and very God,—as Marcion does, as Manichæus does, and other pests of similar opinions. On this account (that I may put into as brief a space as I can what my own views are on the subject), as much injury is done to the New Testament, when it is put on the same level with the Old Testament, as is inflicted on the Old itself when men deny it to be the work of the supreme God of goodness.”

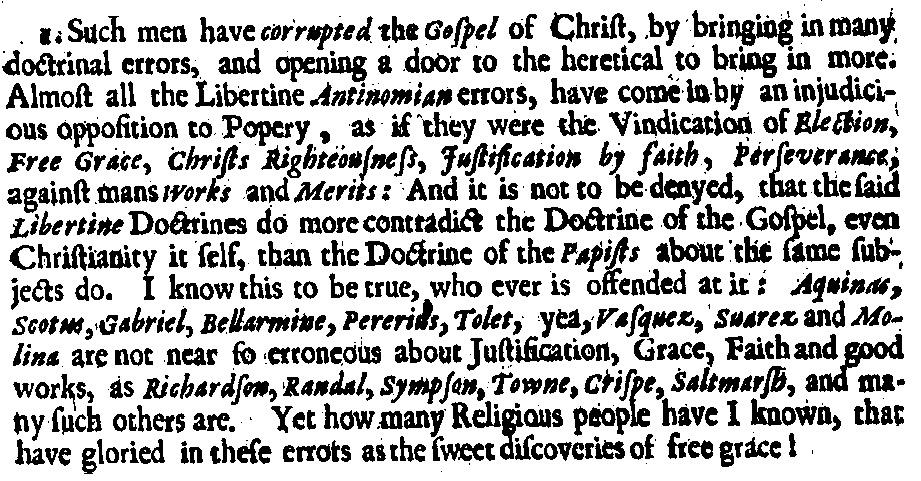

That Pelagius was correct in seeing the Old Covenant as a law of works was assumed throughout Augustine’s writings. Pelagius’ error was that he did not recognize the typology involved in the fact that the Old Covenant was limited to earthly promises and he believed the New Covenant was a continuation of the same law of works. For Augustine, then, the difference between the Old and the New Covenants was the difference between law and gospel, as well as the difference between earthly and heavenly.

Lutherans

Moving forward a millennium, Augustinian monk Martin Luther articulated the same concept. “For the old testament given through Moses was not a promise of forgiveness of sins or of eternal things, but of temporal things, namely, of the land of Canaan, by which no man was renewed in spirit to lay hold on the heavenly inheritance. Wherefore also it was necessary that, as a figure of Christ, a dumb beast should be slain, in whose blood the same testament might be confirmed, as the blood corresponded to the testament and the sacrifice corresponded to the promise. But here Christ says ‘the new testament in my blood’ [Luke 22:20; I Cor. 11:25], not somebody else’s, but his own, by which grace is promised through the Spirit for the forgiveness of sins, that we may obtain the inheritance.”[11] Philip Melanchthon agreed. “I consider the Old Testament a promise of material things linked up with the demands of the law. For God demands righteousness through the law and also promises its reward, the Land of Canaan, wealth, etc… By contrast, the New Testament is nothing else than the promise of all good things without regard to the law and with no respect to our own righteousness… Jer, ch.31, indicates this difference between the Old and New Testaments.”[12]

Reformed

Once the reformation began to address Anabaptist criticisms of infant baptism we start to see a shift away from Augustine’s view. Joshua Moon notes “looming over all of the Swiss Reformed discussions of Jer 31:31-34 is the dispute with the Anabaptists.”[13]

Bullinger’s central solution to the Anabaptist arguments, as for Zwingli, rests in a particular view of the continuity and sufficiency of the Old Testament. In the treatise Bullinger aims to establish that there is one single covenant of God that has always been in operation: the same essence, with the same basic requirements (faith and love), even if with different accompaniments. The payoff is the continuity of the way in which God deals with the children of believers – at least as far as baptism.[14]

The contrast between the Old and the New, according to Bullinger, referred only to the “accidents.”

[T]he nomenclature of the old and new covenant, spirit, and people did not arise from the very essence (substantia) of the covenant but from certain foreign and unessential things (accidentibus) because the diversity of the times recommended that now this, now that be added according to the [difference] of the Jewish people. These additions (accessere) did not exist as perpetual and particularly necessary things for salvation, but they arose as changeable things according to the time, the persons, and the circumstances. The covenant itself could easily continue without them.[15]

Moon notes “Bullinger’s reading, and the positing of a unity of substance and contrast of accidents, shows what will emerge as the boundary markers of Reformed thought on the subject. Such language becomes common for the Reformed and will influence the whole of the tradition through the period of orthodoxy and into the contemporary Reformed world.”[16] That said, “The difficulty of limiting the contrast in the oracle [Jer. 31] to ‘accidents’, however, will be felt by a number of the Reformed.”[17]

Calvin

Following in this same line, Calvin’s treatment of the topic in his Institutes is framed as a response to Anabaptist arguments.

This discussion, which would have been most useful at any rate, has been rendered necessary by that monstrous miscreant, Servetus, and some madmen of the sect of the Anabaptists, who think of the people of Israel just as they would do of some herd of swine, absurdly imagining that the Lord gorged them with temporal blessings here, and gave them no hope of a blessed immortality.[18]

It is a bit difficult to confirm Calvin’s summary of the Anabaptists with their own statements for two reasons. First, the label Anabaptist was applied broadly to all radical reformers with a wide variety of beliefs.[19] “For polemical purposes, Calvin often loosely placed all the sectarians in one group.”[20] Second, Anabaptist writings are much more scarce than reformed literature (perhaps because many of the Anabaptists did not defend their ideas in writing, but preferred the “Apostolic” method of oral discourse, making it more difficult to determine what precisely they believed).[21] Willem Balke notes “It is difficult to trace all of the sources from which Calvin drew his information about the Anabaptists.”[22] Calvin had a great deal of first-hand experience with Anabaptists throughout his life, including strategically joining a tailor’s guild in Strasbourg where “nearly all members were Anabaptists.”[23] He even married the widow of one ex-Anabaptist that he had converted after he debated him publicly.[24]

Far from a tangential debate, Anabaptism was an integral part of the development of Calvin’s theology. “He defined his theological position with two distinct foils in mind ‐ Rome and the Radicals.”[25] “In 1539, Calvin provided a much broader theological exposition for his polemic against the Anabaptists. His controversy with them occasioned much of the overall expansion of the Institutes.”[26] Neither was his debate with Anabaptists merely an academic exercise. In the eyes of Calvin and other reformers, the very success of the Reformation hinged upon whether they could refute the Anabaptists,[27] and Calvin was seen as the very best hope of doing so.[28]

Neither was this task an impersonal one. The Anabaptists were a consistent political and personal thorn in Calvin’s flesh throughout his ministry. Calvin’s exile from France was a result of being lumped with Anabaptists himself.

From the perspective of [King] Francis, all Protestants—including everyone from Antoine Marcourt, the architect of the placards incident, to Lutherans to Calvin—were, like the German Anabaptists, a threat to political harmony. One might say fairly that Calvin spent the rest of his life trying to distance himself from this distasteful comparison, and he himself admitted as much in the preface to his commentary on the Psalms. Through the final edition of the Institutes of the Christian Religion in 1559 and until his death five years later, Calvin never ceased instituting “true religion” in opposition to what he, no less than Francis, thought to be Anabaptist extremism.[29]

His exile from Geneva was also directly related to Anabaptists.[30] Calvin wrote a confession that denounced Anabaptism and required all the citizens of Geneva to personally swear an oath affirming it, or be banished. The Anabaptists refused but the Geneva Council was reluctant to enforce the banishment. Calvin warned the Council that he would excommunicate the Anabaptists from the church if they refused the confession. The Council forbid him to do so. “In the midst of the conflict and confusion, Calvin and Farel refused to administer the Lord’s Supper on Easter. Demonstrations developed in the streets and emergency meetings of the Council were held. Three days later the decision came: Calvin and Farel were expelled from the city.”[31]

And thus “It was the Anabaptists who prompted Calvin, like Zwingli, to reconsider the question of the relationship of the Old Testament to the New Testament. This matter lay close to Calvin’s heart.”[32] “According to Schrenk, Calvin depended on Zwingli and Bullinger with respect to this concept. They were compelled to develop their theology of covenant in their conflicts with the Anabaptists.”[33] “It did not start in Wittenberg or Geneva but in Zurich. For Reformed Theology, Zwingli is the real renewer of the biblical idea of the covenant, but its impulse may have come from the Anabaptist side. Bullinger gave this Zwinglian doctrine its first design. The struggle against the Anabaptists and the desire to establish a national church are the driving forces behind this thought.”[34]

“[T]he doctrine of the covenant was critically important as a basis for infant baptism. [Calvin] fully developed his ideas in this regard in the Institutes. His line of reasoning focuses entirely on this fundamental concept.”[35] “With the obvious intention of refuting Anabaptism, he added an entire chapter on the relationship between the Old and New Testament, which became the most significant basis for his defense of infant baptism.”[36]

With regards to the Old and New covenants, Calvin finds himself in an interesting situation. The Anabaptists appear to be in agreement with Augustine and the Lutherans that the Old Covenant was limited to earthly promises, but they would appear to disagree that those blessings revealed the gospel in types and shadows during the Old Testament era and thereby saved Old Testament saints through the New Covenant.[37] Calvin could refute their error on this point by arguing, like Augustine, that the New Covenant was also operative during the Old Testament era, and therefore Israelites did have a hope of blessed immortality. Though adopting Augustine’s view would be entirely sufficient to establish the point, it would not leave Calvin with any defense of infant baptism because it does not entail that the Old and New Covenants are one. Peter Lillback explains

Calvin both presents his case for paedobaptism as well as defends it against various attacks by employment of the covenant idea. His positive arguments build initially upon his already established point of the continuity of the Old and New Covenants. It is due to the continuity of the covenant with the Jews and with Christians that enables Christians to baptize their infants.[38]

However, various “passages seem to argue that there is not one divine covenant throughout Scripture, but rather that there are two of quite a different character. Should that interpretation be correct, then Calvin would be forced to concede the argument to the Anabaptists after all. How can he explain this difference and still maintain the continuity of the Covenants?”[39] Therefore, instead of refuting the Anabaptists with Augustine’s argument, Calvin addresses this point by appeal to the anti-Anabaptist argument from covenant unity established by Bullinger. “The covenant made with all the fathers is so far from differing from ours in reality and substance, that it is altogether one and the same: still the administration differs.”[40]

In Book 2, Chapter 10 of the Institutes, he outlines the reasons why “both covenants are truly one… although differently administered”

- The Old Covenant promised eternal life, just like the New.

- The Old Covenant was established in the mercy of God, just like the New.

- The Old Covenant was confirmed by the mediation of Christ, just like the New.

In Chapter 11, Calvin gives “five points of difference between the Old and the New Testaments” which “belong to the mode of administration rather than the substance.”

- “In the Old Testament the heavenly inheritance is exhibited under temporal blessings; in the New, aids of this description are not employed.”

- “The Old Testament typified Christ under ceremonies. The New exhibits the immediate truth and the whole body.”

- “The Old Testament is literal, the New spiritual.”

- “The Old Testament belongs to bondage, the New to liberty.”

- “The Old Testament belonged to one people only, the New to all.”

Calvin’s Similarities

Regarding the similarities, Calvin says the first point is “the foundation of the other two” and therefore “a lengthy proof is given of it” taking up most of the chapter. It is “the most pertinent to the present subject, and the most controverted.”[41] To prove that the Old Covenant promised eternal life, Calvin argues

The Apostle, indeed, removes all doubt when he says that the Gospel which God gave concerning his Son, Jesus Christ, ‘he had promised aforetime by his prophets in the holy Scriptures,’ (Rom. 1:2)… Most clearly, therefore, does the Apostle demonstrate that the Old Testament had special reference to the future life, when he says that the promises of the Gospel were comprehended under it.[42]

Based upon this fact, he then argues “we infer that the Old Testament was both established by the free mercy of God and confirmed by the intercession of Christ.”[43]

Calvin further argues “that the spiritual covenant was common also to the Fathers” because their souls were quickened by the “inherent efficacy” of the word of God in the Old Testament. “Adam, Abel, Noah, Abraham, and the other patriarchs, having been united to God by this illumination of the word, I say, there cannot be the least doubt that entrance was given them into the immortal kingdom of God.”[44] He then provides numerous examples showing that these believers aspired to “a better life” elsewhere, making them “pilgrims and strangers in the land of Canaan.”[45]

On this point, there is much overlap with Augustine, but Calvin makes an inference that Augustine does not. Augustine agrees with Calvin that regenerate Israelites were pilgrims, but he says they were pilgrims because they looked beyond the Old Covenant and were thereby counted heirs of the New Covenant. Augustine did not believe this meant the Old and the New were one.

[W]hatever blessings are there figuratively set forth as appertaining to the New Testament require the new man to give them effect… the happy persons, who even in that early age were by the grace of God taught to understand the distinction now set forth, were thereby made the children of promise, and were accounted in the secret purpose of God as heirs of the New Testament; although they continued with perfect fitness to administer the Old Testament to the ancient people of God, because it was divinely appropriated to that people in God’s distribution of the times and seasons.[46]

Contrary to Augustine, based upon the above arguments, Calvin asserts

Let us then lay it down confidently as a truth which no engines of the devil can destroy – that the Old Testament or covenant which the Lord made with the people of Israel was not confined to earthly objects, but contained a promise of spiritual and eternal life, the expectation of which behaved to be impressed on the minds of all who truly consented to the covenant.[47]

But this does not follow. It is an invalid inference to claim that because regenerate Israelites were part of the immortal kingdom of God, therefore the Old and New covenants are one. It does not follow that the Old covenant promised eternal life. Augustine and the Lutherans affirmed that regenerate Israelites were part of the immortal kingdom of God, but they also affirmed that the Old and New were two distinct covenants and that the Old was limited to earthly blessings. Calvin’s inference, which he asserts throughout as foundational, is simply invalid. The correct inference, made by Augustine, is that regenerate Israelites partook of the New covenant. As we will see below, Calvin ends up having to make use of this correct inference when he encounters problems with his argument.

Calvin’s Differences

The first difference between the Old and the New Covenants is that “God was pleased to indicate and typify both the gift of future and eternal felicity by terrestrial blessings, as well as the dreadful nature of spiritual death by bodily punishments, at that time when he delivered his covenant to the Israelites as under a kind of veil.”[48]

The second difference “is in the types, the former exhibiting only the image of truth, while the reality was absent, the shadow instead of the substance, the latter exhibiting both the full truth and the entire body.”[49] Here we begin to see an interesting tension in Calvin’s substance/accidents distinction. Previously he argued that the Old and New are the same in substance, only differing in accidents. But here we are told one difference between them is that the New actually has the substance, while the Old does not.

In regards to Hebrews 7-10, he says that because the typical ceremonies “were the means of administering the covenant, the name of covenant is applied to them, just as is done in the case of other sacraments. Hence, in general, the Old Testament is the name given to the solemn method of confirming the covenant comprehended under ceremonies and sacrifices.” This definition of the term “Old Testament” is important to keep in mind. “Old Testament” refers only to the accidents of the covenant prior to Christ. Calvin then notes that the Old covenant was to be annulled because “there is nothing substantial in it, until we look beyond it” to “Christ, the surety and mediator of a better covenant.”[50] Again we see that the Old Testament lacks the substance it is supposed to share with the New. Here Calvin’s problem is clear. The “Old Testament” refers only to the accidents, but the “New” refers to the substance. Thus the difference between them apparently is not accidents vs accidents, but accidents vs substance.

Calvin is forced into these comparisons, against his earlier framework, because of “the many passages of Scripture in which they are are contrasted as things differing most widely from each other.”[51] In the above, Calvin dealt with Hebrews 7-10, arguing that it was addressing only ceremonies. He next deals with 2 Corinthians 3:5-6 and Jeremiah 31:31-34. While Calvin must attempt to keep these differences on the level of outward administration, we have just seen that he is unable to. As Augustine remarked on these same passages:

I beg of you, however, carefully to observe, as far as you can, what I am endeavouring to prove with so much effort. When the prophet promised a new covenant, not according to the covenant which had been formerly made with the people of Israel when liberated from Egypt, he said nothing about a change in the sacrifices or any sacred ordinances, although such change, too, was without doubt to follow, as we see in fact that it did follow, even as the same prophetic scripture testifies in many other passages; but he simply called attention to this difference, that God would impress His laws on the mind of those who belonged to this covenant, and would write them in their hearts, (Jer 31:32-33) whence the apostle drew his conclusion,—“not with ink, but with the Spirit of the living God; not in tables of stone, but in fleshy tables of the heart;” (2 Cor 3:3)… It is therefore apparent what difference there is between the old covenant and the new,—that in the former the law is written on tables, while in the latter on hearts; so that what in the one alarms from without, in the other delights from within; and in the former man becomes a transgressor through the letter that kills, in the other a lover through the life-giving spirit.[52]

Commenting on Jeremiah 31:31-34 as quoted in Hebrews 8:8, Calvin himself acknowledges the same.

[H]ere the question is respecting ceremonies, but the Prophet speaks of the whole Law: what has it to do with ceremonies, when God inscribes on the heart the rule of a godly and holy life, delivered by the voice and teaching of men? To this I reply that the argument is applied from the whole to a part. There is no doubt but that the Prophet includes the whole dispensation of Moses when he says, “I have made with you a covenant which you have not kept.” Besides, the Law was in a manner clothed with ceremonies; now when the body is dead, what is the use of garments? It is a common saying that the accessory is of the same character with his principal. No wonder, then, that the ceremonies, which are nothing more than appendages to the old covenant, should come to an end, together with the whole dispensation of Moses. Nor is it unusual with the Apostles, when they speak of ceremonies, to discuss the general question respecting the whole Law. Though, then, the prophet Jeremiah extends wider than to ceremonies, yet as it includes them under the name of the old covenant, it may be fitly applied to the present subject.[53]

In other words, because the substance (body) is different, then of course the accidents (garments) will change as well. Note, that this contradicts his argument in the Institutes that in Hebrews 7-10 (which is built upon Jeremiah 31:31-34), “the Old Testament is the name given to the solemn method of confirming the covenant comprehended under ceremonies and sacrifices.” In his commentary on Jeremiah 31, Calvin says “the Prophet speaks of the whole Law… the whole dispensation of Moses… extends wider than to ceremonies”.

Returning to the Institutes, Calvin says that both Jeremiah (31:31-34) and Paul (2 Cor. 3:5-6) “consider nothing in the Law but what is peculiar to it.”[54] Thus he asserts that “Old covenant” in these two passages is referring simply to “the Law” while “New covenant” refers to “the Gospel.” “The Law is designated by the name of the Old, and the Gospel by that of the New Testament.”[55] Properly defining the terms is crucial to Calvin’s position. Calvin insisted that in Heb 7-10, “Old Testament” referred only to the typical ceremonies. Here he insists it refers to “the Law.” But what precisely does Calvin mean by “the Law” in this instance? Does he mean the moral law? Does he mean the books of Moses? Does he mean Mosaic law as a whole (moral, judicial, ceremonial), delivered on Mt. Sinai? It’s not immediately clear.

the Law here and there contains promises of mercy; but as these are adventitious to it, they do not enter into the account of the Law as considered only in its own nature. All which is attributed to it is, that it commands what is right, prohibits crimes, holds forth rewards to the cultivators of righteousness, and threatens transgressors with punishment, while at the same time it neither changes nor amends that depravity of heart which is naturally inherent in all.[56]

Broadly speaking, “the Law” contains promises of mercy, but those promises are extrinsic to it. Again, it is not immediately clear what Calvin means by “the Law” in this instance – whether it refers to the writings of Moses or to the Mosaic Covenant as a whole. He first says “the Law” contains promises of mercy, then he says that it does not. If by “the Law” Calvin means the moral law, then he is incorrect because it does not contain any promises of mercy, not even “adventitiously.” If by “the Law” Calvin does not mean simply the moral law, then is he equivocating when he proceeds immediately (“All that is attributed to it is…”) to describe “the Law” in terms of the moral law, arguing that “Jeremiah indeed calls the Moral Law also a weak and fragile covenant”?[57]

Perhaps he means that “the Law” refers to the five books of Moses.[58] Thus promises of mercy are found in the writings of Moses. But that does not make sense of his comment that the promises are adventitious to it. How can part of Moses’ writings be adventitious to Moses’ writings? He later explains that is not what is meant by “the Law” when he says that the Old Testament “is of wider extent [than just the Law] (sec. 1), comprehending under it the promises which were given before the Law” thus identifying the Law with a particular point in history.[59]

The best explanation appears to be that by “the Law” Calvin means the law delivered by God to Israel on Mt. Sinai, including the moral, judicial, and ceremonial law. This would seem to be confirmed by the above statements regarding the moral law, crimes, and the timing, taken together with other statements such as “For the Apostle speaks of the Law more disparagingly than the Prophet. This he does not simply in respect of the Law itself, but because there were some false zealots of the Law who, by a perverse zeal for ceremonies, obscured the clearness of the Gospel”[60] as well as when he works through Paul’s antitheses in 2 Cor 3 and concludes “The last antithesis must be referred to the Ceremonial Law.”[61] This reading is confirmed by Calvin’s earlier statement in chapter 7. “By the Law, I understand not only the Ten Commandments, which contain a complete rule of life, but the whole system of religion delivered by the hand of Moses.”[62] We find this confirmed in his commentary on Jeremiah 31:31-34 as well. “[T]he Prophet speaks of the whole Law… There is no doubt but that the Prophet includes the whole dispensation of Moses.”

Thus the whole Mosaic law delivered on Mt. Sinai to the people of Israel is what Jeremiah and Paul refer to as the Old Covenant. This Old Covenant is contrasted to the Gospel. Promises of mercy may be found here and there in this Old Covenant, but they are adventitious to it because the Old Covenant “neither changes nor amends that depravity of heart which is naturally inherent in all.”[63] Therefore “the Old Testament is literal, because promulgated without the efficacy of the Spirit: the New spiritual, because the Lord has engraven it on the heart.”[64] An example of this is found in Calvin’s commentary on Deuteronomy 30:6. “And the Lord thy God will circumcise thine heart. This promise far surpasses all the others, and properly refers to the new Covenant, for thus it is interpreted by Jeremiah.”[65]

We once again find Calvin depicting the differences between the Old and the New, not as a difference in accidents, but in substance. Calvin previously argued they were the same in substance because they both equally promised eternal life and because the patriarchs were members of the “immortal kingdom of God” through “illumination [regeneration] of the word.”[66] Now, because he is explaining the meaning of Jeremiah, Paul, and the author of Hebrews, Calvin says the exact opposite: the promise of mercy is adventitious to the Old covenant and the Old covenant regenerates no one. How can Calvin speak so contradictorily?[67] As we will see below, it is because he is defining “Old covenant” differently in each instance. Joshua Moon notes “The only way in which he is able to do this without blatant contradiction is through the broadening of the term ‘Old Testament’ in the first of the comparisons, as he admits to doing (‘The first extends more widely…’).”[68]

Calvin’s fourth difference is that “The Old Testament belongs to bondage, the New to liberty.” Referencing Heb 12:18-22 and Gal 4:25-26, Calvin says “The Old Testament filled the conscience with fear and trembling – The New inspires it with gladness.” Echoing the previous point, Calvin affirms that the holy fathers shared in the liberty from bondage, but explains that this freedom was not derived from “the Law.”[69] Commenting on this, Peter Lillback notes “Calvin’s explanation once again indicates his understanding of the New Covenant as the place of salvation in all of redemptive history.”[70]

He concludes “The three last contrasts to which we have adverted (sec. 4, 7, 9) are between the Law and the Gospel, and hence in these the Law is designated by the name of the Old, and the Gospel by that of the New Testament.” Note carefully that by this Calvin considers the typical ceremonies of the Old Covenant (difference #2, sec. 4) to fall under “the Law” in contrast to “the Gospel” even though they reveal the Gospel typologically. He says that the holy fathers

were under the same bonds and burdens of observances as the rest of their nation. Therefore, seeing they were obliged to the anxious observance of ceremonies (which were the symbols of a tutelage bordering on slavery, and handwritings by which they acknowledged their guilt, but did not escape from it), they are justly said to have been, comparatively, under a covenant of fear and bondage, in respect of that common dispensation under which the Jewish people were then placed.[71]

Calvin re-visited this issue in his commentary on the book of Hebrews, where he again wrestles with Jeremiah’s stark contrast.

But what he adds is not without some difficulty, — that the covenant of the Gospel was proclaimed on better promises; for it is certain that the fathers who lived under the Law had the same hope of eternal life set before them as we have, as they had the grace of adoption in common with us, then faith must have rested on the same promises. But the comparison made by the Apostle refers to the form rather than to the substance; for though God promised to them the same salvation which he at this day promises to us, yet neither the manner nor the character of the revelation is the same or equal to what we enjoy.[72]

Again Calvin attempts to explain the difference as a matter of form or outward administration. The difference is the manner and character of the revelation (i.e. obscure vs. clear). But in expositing the text, Calvin runs into his recurring dilemma. “There are two main parts in this covenant; the first regards the gratuitous remission of sins; and the other, the inward renovation of the heart.”[73] This presents Calvin with the problem of how these two things can be attributed to the New covenant in contrast to the Old. He argues it was simply a matter of degree (lesser vs greater), as well as clarity.

But it may be asked, whether there was under the Law a sure and certain promise of salvation, whether the fathers had the gift of the Spirit, whether they enjoyed God’s paternal favor through the remission of sins? Yes, it is evident that they worshipped God with a sincere heart and a pure conscience, and that they walked in his commandments, and this could not have been the case except they had been inwardly taught by the Spirit; and it is also evident, that whenever they thought of their sins, they were raised up by the assurance of a gratuitous pardon. And yet the Apostle, by referring the prophecy of Jeremiah to the coming of Christ, seems to rob them of these blessings. To this I reply, that he does not expressly deny that God formerly wrote his Law on their hearts and pardoned their sins, but he makes a comparison between the less and the greater. As then the Father has put forth more fully the power of his Spirit under the kingdom of Christ, and has poured forth more abundantly his mercy on mankind, this exuberance renders insignificant the small portion of grace which he had been pleased to bestow on the fathers. We also see that the promises were then obscure and intricate, so that they shone only like the moon and stars in comparison with the clear light of the Gospel which shines brightly on us.

But this answer is confounded by the fact that Abraham’s faith, far from being less than ours, is the prime example of ours. So it cannot be a difference in degree.

If it be objected and said, that the faith and obedience of Abraham so excelled, that hardly any such an example can at this day be found in the whole world; my answer is this, that the question here is not about persons, but that reference is made to the economical condition of the Church. Besides, whatever spiritual gifts the fathers obtained, they were accidental as it were to their age; for it was necessary for them to direct their eyes to Christ in order to become possessed of them. Hence it was not without reason that the Apostle, in comparing the Gospel with the Law, took away from the latter what is peculiar to the former. There is yet no reason why God should not have extended the grace of the new covenant to the fathers. This is the true solution of the question.[74]

To escape this dilemma, Calvin must abandon his unity of Old and New and flee to Augustine’s view. The true solution is to admit that the saving faith experienced by the fathers was not derived from the Old covenant, but was rather “accidental” to it. Their salvation was a blessing of the New covenant extended back to them.

Was the grace of regeneration wanting to the Fathers under the Law? But this is quite preposterous. What, then, is meant when God denies here that the Law was written on the heart before the coming of Christ? To this I answer, that the Fathers, who were formerly regenerated, obtained this favor through Christ, so that we may say, that it was as it were transferred to them from another source. The power then to penetrate into the heart was not inherent in the Law, but it was a benefit transferred to the Law from the Gospel.[75]

Joshua Moon notes

The borrowing from Augustine is no less strong in these passages than is admitted in the Institutes, and is invoked to resolve the question of the attributes of the member of the new covenant which are clearly evidenced in the ancients. If the new covenant member is identified by the law on the heart, which is regeneration, then those who were regenerate before Christ were members of the new covenant. But Calvin has simply side-stepped the difficulty raised in identifying the law on the heart (regeneration) with the ‘form’ of the covenant.[76]

Calvin’s “Old Testament”

So then what exactly is the Old covenant that Calvin believes is one and the same with the New covenant? He says that “The three last contrasts to which we have adverted (sec. 4, 7, 9), are between the Law and the Gospel, and hence in these the Law is designated by the name of the Old, and the Gospel by that of the New Testament. The first [the Old Testament] is of wider extent (sec. 1) [than the Law], comprehending under it the promises which were given even before the Law.”[77] Calvin is not here arguing that the Old Testament means the Old Scriptures, having been revealed before the Law. Rather, he means that the Old covenant God made with the Israelites on Mt. Sinai includes more than just the Mosaic Law (“the whole system of religion delivered by the hand of Moses”). It also includes promises of eternal life – the same promises which were given prior to the Old covenant. Thus he says “the Old Testament or covenant which the Lord made with the people of Israel was not confined to earthly objects, but contained a promise of spiritual and eternal life, the expectation of which behaved to be impressed on the minds of all who truly consented to the covenant” making it clear he is not simply referring to the Old Scriptures.[78]

Recall from above that Augustine encountered a related argument in Pelagius. He recounts the trial.

After the judges had accorded their approbation to this answer of Pelagius, another passage which he had written in his book was read aloud: “The kingdom of heaven was promised even in the Old Testament.” Upon this, Pelagius remarked in vindication: “This can be proved by the Scriptures: but heretics, in order to disparage the Old Testament, deny this. I, however, simply followed the authority of the Scriptures when I said this; for in the prophet Daniel it is written: ‘The saints shall receive the kingdom of the Most. High.’” (Dan 7:18) After they had heard this answer, the synod said: “Neither is this opposed to the Church’s faith.”[79]

Augustine then replied:

Was it therefore without reason that our brethren were moved by his words to include this charge among the others against him? Certainly not. The fact is, that the phrase Old Testament is constantly employed in two different ways,—in one, following the authority of the Holy Scriptures; in the other, following the most common custom of speech.

For the Apostle Paul says, in his Epistle to the Galatians: “Tell me, ye that desire to be under the law, do ye not hear the law? For it is written that Abraham had two sons, the one by a bond-maid, the other by a free woman… Which things are an allegory: for these are the two testaments; the one which gendereth to bondage, which is Agar. For this is Mount Sinai in Arabia, and is conjoined with the Jerusalem which now is, and is in bondage with her children; whereas the Jerusalem which is above is free, and is the mother of us all.” (Gal 4:21-26)

Now, inasmuch as the Old Testament belongs to bondage, whence it is written, “Cast out the bond-woman and her son, for the son of the bond-woman shall not be heir with my son Isaac,” (Gal 4:30) but the kingdom of heaven to liberty; what has the kingdom of heaven to do with the Old Testament? Since, however, as I have already remarked, we are accustomed, in our ordinary use of words, to designate all those Scriptures of the law and the prophets which were given previous to the Lord’s incarnation, and are embraced together by canonical authority, under the name and title of the Old Testament, what man who is ever so moderately informed in ecclesiastical lore can be ignorant that the kingdom of heaven could be quite as well promised in those early Scriptures as even the New Testament itself, to which the kingdom of heaven belongs?

At all events, in those ancient Scriptures it is most distinctly written: “Behold, the days come, saith the Lord, that I will consummate a new testament with the house of Israel and with the house of Jacob; not according to the testament that I made with their fathers, in the day that I took them by the hand, to lead them out of the land of Egypt.” (Jer 31:31, 32) This was done on Mount Sinai. But then there had not yet risen the prophet Daniel to say: “The saints shall receive the kingdom of the Most High.” (Dan 7:18) For by these words he foretold the merit not of the Old, but of the New Testament. In the same manner did the same prophets foretell that Christ Himself would come, in whose blood the New Testament was consecrated. Of this Testament also the apostles became the ministers, as the most blessed Paul declares: “He hath made us able ministers of the New Testament; not in its letter, but in spirit: for the letter killeth, but the spirit giveth life.” (2 Cor 3:6)

In that testament, however, which is properly called the Old, and was given on Mount Sinai, only earthly happiness is expressly promised. Accordingly that land, into which the nation, after being led through the wilderness, was conducted, is called the land of promise, wherein peace and royal power, and the gaining of victories over enemies, and an abundance of children and of fruits of the ground, and gifts of a similar kind are the promises of the Old Testament. And these, indeed, are figures of the spiritual blessings which appertain to the New Testament; but yet the man who lives under God’s law with those earthly blessings for his sanction, is precisely the heir of the Old Testament, for just such rewards are promised and given to him, according to the terms of the Old Testament, as are the objects of his desire according to the condition of the old man.

But whatever blessings are there figuratively set forth as appertaining to the New Testament require the new man to give them effect. And no doubt the great apostle understood perfectly well what he was saying, when he described the two testaments as capable of the allegorical distinction of the bond-woman and the free,—attributing the children of the flesh to the Old, and to the New the children of the promise: “They,” says he, “which are the children of the flesh, are not the children of God; but the children of the promise are counted for the seed.” (Rom 9:8) The children of the flesh, then, belong to the earthly Jerusalem, which is in bondage with her children; whereas the children of the promise belong to the Jerusalem above, the free, the mother of us all, eternal in the heavens. (Gal 4:25, 26) Whence we can easily see who they are that appertain to the earthly, and who to the heavenly kingdom. But then the happy persons, who even in that early age were by the grace of God taught to understand the distinction now set forth, were thereby made the children of promise, and were accounted in the secret purpose of God as heirs of the New Testament; although they continued with perfect fitness to administer the Old Testament to the ancient people of God, because it was divinely appropriated to that people in God’s distribution of the times and seasons.

How then should there not be a feeling of just disquietude entertained by the children of promise, children of the free Jerusalem, which is eternal in the heavens, when they see that by the words of Pelagius the distinction which has been drawn by Apostolic and catholic authority is abolished, and Agar is supposed to be by some means on a par with Sarah? He therefore does injury to the scripture of the Old Testament with heretical impiety, who with an impious and sacrilegious face denies that it was inspired by the good, supreme, and very God,—as Marcion does, as Manichæus does, and other pests of similar opinions. On this account (that I may put into as brief a space as I can what my own views are on the subject), as much injury is done to the New Testament, when it is put on the same level with the Old Testament, as is inflicted on the Old itself when men deny it to be the work of the supreme God of goodness.[80]

Augustine says that “following the most common custom of speech” we can say that the Old Testament promised eternal life because by “Old Testament” we simply mean “all those Scriptures of the law and the prophets which were given previous to the Lord’s incarnation.” However, if we properly define the Old Testament “following the authority of the Holy Scriptures” as the covenant that was “given on Mount Sinai” to “the ancient people of God” then “only earthly happiness is expressly promised.” He goes so far as to say that claiming the Old and the New covenants offer the same promise “does injury to the scripture of the Old Testament with heretical impiety.”

Calvin was aware of Augustine’s objection to his position.

When Augustine maintained that [the promises of eternal life] were not to be included under the name of the Old Testament (August. ad Bonifac. lib. 3 c. 14), he took a most correct view, and meant nothing different from what we have now taught; for he had in view those passages of Jeremiah and Paul in which the Old Testament is distinguished from the word of grace and mercy. In the same passage, Augustine, with great shrewdness remarks, that from the beginning of the world the sons of promise, the divinely regenerated, who, through faith working by love, obeyed the commandments, belonged to the New Testament; entertaining the hope not of carnal, earthly, temporal, but spiritual, heavenly, and eternal blessings, believing especially in a Mediator, by whom they doubted not both that the Spirit was administered to them, enabling them to do good, and pardon imparted as often as they sinned. The thing which he thus intended to assert was, that all the saints mentioned in Scripture, from the beginning of the world, as having been specially selected by God, were equally with us partakers of the blessing of eternal salvation. The only difference between our division and that of Augustine is, that ours (in accordance with the words of our Saviour, “All the prophets and the law prophesied until John,” Mt. 11:13) distinguishes between the gospel light and that more obscure dispensation of the word which preceded it, while the other division simply distinguishes between the weakness of the Law and the strength of the Gospel. And here also, with regard to the holy fathers, it is to be observed, that though they lived under the Old Testament, they did not stop there, but always aspired to the New, and so entered into sure fellowship with it.[81]

Calvin defends himself by claiming by “Old Testament” he means “all the prophets and the law” – that is, the Scriptures prior to Christ. In which case, the only difference between the two is the degree of clarity, and thus a difference in administration. But as we have just seen, that is not in fact how Calvin has been using the term. He again side-steps the issue and does not answer Augustine. Moon notes “The necessary equivocations … show the incompatibility of [Calvin’s] approach.”[82]

In sum, Calvin’s position hinges upon how one defines the Old covenant. If we define it according to Jeremiah, Paul, and the author of Hebrews as “the whole system of religion delivered by the hand of Moses,”[83] then the difference between the Old and New is the difference between Law and Gospel, and thus Augustine is correct (according to Calvin) that eternal salvation is found in the New covenant alone. However, if Jeremiah, Paul, and the author of Hebrews were improperly abstracting only one part of the Old Covenant, which is defined as something other than “the whole system of religion delivered by the hand of Moses” or “the whole dispensation of Moses”[84] and the Old covenant itself promises eternal life, then the Old and New are really one and the same covenant.

Owen

After more than a century of development, the reformed view articulated by Bullinger, Calvin, and others became solidified in the Westminster Confession.[85] However, not all reformed theologians were happy with the position. Ironically, chief among these dissenters was the “Calvin of England” John Owen.[86] There appears to be development in his thought over the years, but it finds its fullest expression on this question in his several thousand page magnum opus, An Exposition of the Epistle to the Hebrews. It is there, in over 150 pages of meticulous analysis of the logic of Jeremiah and the author of Hebrews on 8:6-13 that Owen finds reason to reject Calvin’s view and return instead to Augustine’s.

Here then ariseth a difference of no small importance, namely, whether these are indeed two distinct covenants, as to the essence and substance of them, or only different ways of the dispensation and administration of the same covenant. And the reason of the difficulty lieth herein: We must grant one of these three things:

- That either the covenant of grace was in force under the old testament; or,

- That the church was saved without it, or any benefit by Jesus Christ, who is the mediator of it alone; or,

- That they all perished everlastingly.And neither of the two latter can be admitted…

I shall take it here for granted, that no man was ever saved but by virtue of the new covenant, and the mediation of Christ therein.

Suppose, then, that this new covenant of grace was extant and effectual under the old testament, so as the church was saved by virtue thereof, and the mediation of Christ therein, how could it be that there should at the same time be another covenant between God and them, of a different nature from this, accompanied with other promises, and other effects?

On this consideration it is said, that the two covenants mentioned, the new and the old, were not indeed two distinct covenants, as unto their essence and substance, but only different administrations of the same covenant, called two covenants from some different outward solemnities and duties of worship attending of them…

But on the other hand, there is such express mention made, not only in this, but in sundry other places of the Scripture also, of two distinct covenants, or testaments, and such different natures, properties, and effects, ascribed unto them, as seem to constitute two distinct covenants…

The judgment of most reformed divines is, that the church under the old testament had the same promise of Christ, the same interest in him by faith, remission of sins, reconciliation with God, justification and salvation by the same way and means, that believers have under the new. And whereas the essence and the substance of the covenant consists in these things, they are not to be said to be under another covenant, but only a different administration of it. But this was so different from that which is established in the gospel after the coming of Christ, that it hath the appearance and name of another covenant… See Calvin. Institut. lib. 2:cap. xi…

The Lutherans, on the other side, insist on two arguments to prove, that not a twofold administration of the same covenant, but that two covenants substantially distinct, are intended in this discourse of the apostle…[87]

After setting up the dilemma and accurately representing the two possible orthodox positions, Owen gives his opinion.

[T]he Scripture doth plainly and expressly make mention of two testaments, or covenants, and distinguish between them in such a way, as what is spoken can hardly be accommodated unto a twofold administration of the same covenant. The one is mentioned and described, Exodus 24:3-8, Deuteronomy 5:2-5, — namely, the covenant that God made with the people of Israel in Sinai; and which is commonly called “the covenant,” where the people under the old testament are said to keep or break God’s covenant; which for the most part is spoken with respect unto that worship which was peculiar thereunto. The other is promised, Jeremiah 31:31-34, 32:40; which is the new or gospel covenant, as before explained, mentioned Matthew 26:28; Mark 14:24. And these two covenants, or testaments, are compared one with the other, and opposed one unto another, 2 Corinthians 3:6-9; Galatians 4:24-26; Hebrews 7:22, 9:15-20.

These two we call “the old and the new testament.” Only it must be observed, that in this argument, by the “old testament,” we do not understand the books of the Old Testament, or the writings of Moses, the Psalms, and the Prophets, or the oracles of God committed then unto the church… for this old covenant, or testament, whatever it be, is abrogated and taken away, as the apostle expressly proves, but the word of God in the books of the Old Testament abideth for ever.[88]

Owen understood very well what the central issue was: how to define the Old Covenant. Owen concludes, with the Lutherans and against Calvin, that Jer 31:31-34, 2 Cor 3:6-9, Gal 4:24-26, and Hebrews 7:22, 9:5-20 use the term “Old covenant” properly, not improperly. They define what the Old Covenant is. It is “the covenant that God made with the people of Israel in Sinai” in contrast to the “gospel covenant,” according to the authority of Scripture.

He continues:

Wherefore we must grant two distinct covenants, rather than a twofold administration of the same covenant merely, to be intended. We must, I say, do so, provided always that the way of reconciliation and salvation was the same under both. But it will be said, —and with great pretense of reason, for it is that which is the sole foundation they all build upon who allow only a twofold administration of the same covenant, —’That this being the principal end of a divine covenant, if the way of reconciliation and salvation be the same under both, then indeed are they for the substance of them but one.’ And I grant that this would inevitably follow, if it were so equally by virtue of them both. If reconciliation and salvation by Christ were to be obtained not only under the old covenant, but by virtue thereof, then it must be the same for substance with the new. But this is not so; for no reconciliation with God nor salvation could be obtained by virtue of the old covenant, or the administration of it, as our apostle disputes at large, though all believers were reconciled, justified, and saved, by virtue of the promise, whilst they were under the covenant…. the covenant of grace is called “the new covenant,”[89]

Owen again pinpoints the central issue: Calvin’s first argument for the unity of the Old and the New from the salvation of the patriarchs. He recognizes the error in Calvin’s logic. It is false to argue that because an Israelite was saved, therefore the Old and the New are one. The correct inference, following Augustine, is that the Israelite was saved by the New covenant.

The greatest and utmost mercies that God ever intended to communicate unto the church, and to bless it withal, were enclosed in the new covenant. Nor doth the efficacy of the mediation of Christ extend itself beyond the verge and compass thereof; for he is only the mediator and surety of this covenant.[90]

Owen also agreed with Augustine and the Lutherans that the Old Covenant was limited to temporal blessings.

This covenant thus made, with these ends and promises, did never save nor condemn any man eternally. All that lived under the administration of it did attain eternal life, or perished for ever, but not by virtue of this covenant as formally such. It did, indeed, revive the commanding power and sanction of the first covenant of works; and therein, as the apostle speaks, was “the ministry of condemnation,” 2 Corinthians: 3:9; for “by the deeds of the law can no flesh be justified.” And on the other hand, it directed also unto the promise, which was the instrument of life and salvation unto all that did believe. But as unto what it had of its own, it was confined unto things temporal. Believers were saved under it, but not by virtue of it. Sinners perished eternally under it, but by the curse of the original law of works.[91]

In conclusion, Owen denied that the Old and New covenants are of the same substance.

This is the nature and substance of that covenant which God made with that people; a particular, temporary covenant it was, and not a mere dispensation of the covenant of grace.[92]

Owen was at liberty to disagree with the reformed view and instead affirm that Jeremiah, Paul, and the author of Hebrews correctly identified the Old Covenant because refuting the Anabaptists was not his chief concern. One could say exegeting Hebrews was. Owen did not face any significant Anabaptist presence in England in his day. He did, however, encounter many Particular (“reformed”) Baptists, who were altogether different than Calvin’s Anabaptists.[93] Rather than “frantic,” “hairbrained,” “crazy zealot,” “lunatic,” “drunkard,” “heretical” “vermin” who were “enemies of God and of the human race”[94] Owen found co-laborers for Christ, common allies in Congregationalism’s view of the church as a gathering of visible saints, and fellow-sufferers in Non-Conformity. He even found among these baptists a preacher so powerful that Owen told the King of England he would “willingly relinquish all [his] learning” if only he could “possess the tinker’s ability for preaching.”[95] He has been described as “a friend of baptists.”[96] Working alongside baptists in government-appointed committees, “Owen likely discovered that his new colleagues were actually more orthodox than he had suspected, and indeed that their position, especially in ecclesiological terms, was far closer to his than was that of the Presbyterian party with whom he had formerly been linked.”[97]

His Vindication of a Treatise on Schism in 1657 refused to admit that those who renounced and repeated the baptism they received as infants should be described as schismatic. In the face of widespread criticism, Owen defended baptists from the charge of repeating the Donatist heresy… Owen refused to criticize them. Time and time again, Owen defended baptists from their critics.[98]

Refuting credobaptism simply was not the concern for Owen that it was for Calvin and the 16th century reformed.

1689 Federalism

Neither was refuting credobaptism a concern for the 17th century Particular Baptists. They thus came to the same conclusions as Owen regarding the Old and New covenants. Nehemiah Coxe, the probable editor of the Second London Baptist Confession (1677), wrote one of the few systematic particular baptist treatments of covenant theology (as opposed to a merely polemical work). He wrote on covenants in general, the Covenant of Works, the Noahic Covenant, and the Abrahamic Covenant. But when he came to the Old and New Covenants, he felt no need to write his own treatment.

That notion (which is often supposed in this discourse) that the Old Covenant and the New do differ in substance, and not in the manner of their administration only, doth indeed require a more large and particular handling to free it from those prejudices and difficulties that have been cast upon it by many worthy persons, who are otherwise minded. I designed to have given a further account of it in a discourse of the covenant made with Israel in the Wilderness, and the state of the church under the Law. But when I had finished this, and provided some materials also for what was to follow, I found my labour for the clearing and asserting of that point, happily prevented, by the coming for of Dr. Owen’s 3d vol. upon the Hebrews. There it is discussed at length and the objections that seem to lie against it are fully answered, especially in the exposition of the eighth chapter.[99]

This position goes by the name of “1689 Federalism” today, in reference to the Second London Baptist Confession, popularly referred to as the 1689 London Baptist Confession.[100]

Conclusion

We have seen that Augustine offered an orthodox interpretation of the Old and New covenants as two distinct, contrasting covenants. This view was held in various forms through the middle ages[101] and was continued by the Lutherans. Andrew A. Woolsey notes that “Of all the fathers, the favourite of the Reformers was Augustine. John T. McNeill says that ‘Calvin’s self-confessed debt to Augustine is constantly apparent’ throughout the Institutes, and he proves his point in the “Author and Source Index” by listing 730 references to the Bishop of Hippo’s works.”[102] However, Calvin and the reformed tradition departed from Augustine on the question of the Old and New covenants in an attempt to defend infant baptism. This led them into various tensions and inconsistencies and required Calvin to argue that the Old Covenant was something other than “the whole system of religion delivered by the hand of Moses.” These problems were eventually resolved when Owen rejected their innovations and returned to Augustine’s historic interpretation.

Calvin never offered an argument against 1689 Federalism’s view of the Old and New Covenants. Rather, he called its observations very shrewd and “most correct,” affirming 1689 Federalism’s belief that Old Testament saints were members of the New covenant,[103] going so far as to say it is “the real solution to the problem.”[104]

Are the promises of eternal life “to be included under the name of Old Testament”? Augustine and Owen said no. Calvin said they are correct if we define “Old Testament” according to “those passages of Jeremiah and Paul.” But Calvin chose not to do so. Instead, he argued that the Old Testament should be defined as the Law, in contrast to the Gospel, together with the Gospel. In other words, Calvin rejected Scripture’s definition of the Old Testament in favor of a self-contradictory definition of his own, all in an effort to defend infant baptism. And whenever this led him into further contradictions, he abandoned his definition and returned to Augustine’s – which was Jeremiah’s and Paul’s. It would thus appear that a biblical understanding of the Old and New covenants requires one to retain the aspects of Calvin’s interpretation that coincide with Augustine’s, and discard the rest.

[1] Andrew A. Woolsey ”The Covenant in the Church Fathers,” Haddington House Journal, 2003; 38.

[2] ibid, 40

[3] Augustine, A Treatise on the Spirit and the Letter, ch. 36, 41. Augustine, A Work on the Proceedings of Pelagius, ch. 14.

[4] Augustine, A Treatise Against Two Letters of the Pelagians, bk. III ch. 7

[5] ibid, III.11

[6] A Treatise on the Spirit and the Letter, ch. 40

[7] Woolsey, 42-43

[8] Pentiuc, Eugen J. The Old Testament in Eastern Orthodox Tradition. Oxford UP, 2014, 38

[9] A Work on the Proceedings of Pelagius, ch. 13

[10] Pentiuc, 38.

[11] Luther, The Babylonian Captivity of the Church.

[12] Melanchthon, Loci (1521), 120-121. Quoted in Moon, 79.

[13] Joshua Moon, Restitutiuo ad Integrum: An ‘Augustinian’ Reading of Jeremiah 31:31-34 in Dialogue with the Christian Tradition (PhD dissertation, St Mary’s College, University of St Andrews, 2007), 86.

[14] ibid, 88-89.

[15] Bullinger, “Brief Exposition,” 120. Quoted in Moon, 89.

[16] Moon, 93-94.

[17] ibid, 94.

[18] Calvin, John (2011-01-28). Calvin: The Institutes of the Christian Religion (best navigation with Direct Verse Jump) (p. 677). OSNOVA. Kindle Edition. 2.10.1. Editor’s note: “The French is, “Veu qu’ils pensent qu notre Seigneur l’ait voulu seulement engraisser enterre comme en une auge, sans seperance aucune de l’immortalité celeste;” — seeing they think that our Lord only wished to fatten them on the earth as in a sty, without any hope of heavenly immortality.”

[19] Galen Johnson The Development of John Calvin’s Doctrine of Infant Baptism in Reaction to the Anabaptists (Mennonite Quarterly Review, Vol. 73, No. 4, Oct. 1999), 808. “Calvin lived in an era of theological confusion, and despite his tireless efforts to promulgate orderliness, he did not always sharply distinguish among non-magisterial reformers or “radical” groups who saw distinctions among themselves”. Hans Rudolf Lavater Calvin, Farel, and the Anabaptists: On the Origins of the Brieve Instruction of 1544 (Mennonite Quarterly Review, Vol. 88, July 2014, trans. John D. Roth), 323-324 “According to Karl H. Wyneken, Calvin used these labels to characterize ‘radicals‛ in general, even though, as George H. Williams has made clear, the terms did not provide a clear profile of his opponents. In the words of Williams, ‘the Radical Reformation was a loosely interrelated congeries of reformations and restitutions which, besides the Anabaptists of various types, included Spiritualists and spiritualizers of varying tendencies, and the Evangelical Rationalists, largely Italian in origin.‛” Willem Balke Calvin and the Anabaptist Radicals (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1981), 2. “It should be observed that it is not easy to characterize the Anabaptists or to distinguish them accurately from other Radicals such as the Spiritualists, the Fanatics, and the Antitrinitarians. The radicalism of the sixteenth century was a very complex phenomenon. Scholarly discussions concerning it offer so many different interpretations that we cannot expect a common opinion to emerge in Anabaptist scholarship in the near future.”

[20] Balke, 31.

[21] Alejandro Zorzin Reformation Publishing and Anabaptist Propaganda: Two Contrasting Communication Strategies for the Spread of the Anabaptist Message in the Early Days of the Swiss Brethren (Mennonite Quarterly Review, Issue 82, Oct. 2008), 503-516.

[22] Balke, 12.

[23] Lavater, 331.

[24] Lavater, 332.

[25] Balke, 213.

[26] ibid, 121.

[27] “[T]he young republic [Geneva] was being compromised and threatened. The conflicting parties were of approximately equal strength. The Reformation was barely a reality; many within the city did not respect it, while many outside the city slandered it. There was a legitimate fear in Europe that the rebellious Geneva would become the home for Anabaptism and anarchism. Many felt that the emperor should take strong measures against Geneva, as he had done in Munster…” Balke, 75. According to Calvin, “They destroy the unity of the church and discredit the evangelical doctrine in the eyes of government. They are thus a danger for the pursuit of the Reformation.” Balke, 331.

[28] “When Calvin, traveling through, stopped briefly in Geneva, Farel called on him for help. He put the call squarely to Calvin and impressed on him that God would curse him if he

did not stay. Farel swore that Calvin was the man to complete the work of reformation in Geneva. Calvin himself acknowledged that he agreed to stay because he was ‘overcome with fear.’” Balke, 76. “[O]ur colleagues think that a refutation is needed… They ask you, for God’s sake, that you take on this task… I suppose that we could ask someone else to accept this service, but tell us please: who could we find who could take up such a task… with your argumentative gifts or who could accomplish it as artfully as you?” Farel’s letter to Calvin, quoted in Lavatory, 333-334.

[29] Johnson, 804 “In this preface (1557), Calvin recalled that the French government of Francis I persecuted only those considered to be “Anabaptists and seditious persons,” but among them were many whom Calvin considered “faithful and holy.” Thus, Calvin wrote, “This was the consideration which induced me to publish my Institute of the Christian Religion. My objects were, first, to prove that these reports were false and calumnious, and thus to vindicate my brethren, whose death was precious in the sight of the Lord.” John Calvin, Commentary on the Book of Psalms, trans. James Anderson (Grand Rapids, Baker Book House, 1993), 1:xli-xlii (cf. McGrath, Lifeof John Calvin, 76). Indeed, Calvin‟s prefatory letter to Francis in the Institutes (dated August 1, 1535) pressed this very point.” Lavater, 327 “In his Commentary on the Psalms of 1557, Calvin clarified that the actual motivation for the Institutes was the ‘Anabaptists [anabaptistes] and rebels, who with their delusions and erroneous teachings destroy not only religion but also political order.‛” Balke, 70-71 “The fact that the Roman Catholic Church and the French government had lumped the reformers in one category with the Anabaptists moved Calvin to bring out very sharply his differences with the Anabaptists… Finally, of special importance was Calvin’s role in the Institutes as the defender on behalf of his French fellow believers, pleading their innocence against the charges that they were Catabaptists who were dangerous to the state.” Balke, 290 “Since Munster, the charge that the reformers were a danger to the state, just like those Anabaptists, touched a very sore spot with Calvin.”

[30] See Lavater, 328-330 and Balke, 73-95.

[31] Balke, 94.

[32] Balke, 99.

[33] Balke, 312.

[34] G. Schrenk, Gottesreich und Bund im älteren Protestantismus vornehmlich bei Johannes Coccejus (Gutersloh, 1923), pp. 36f. Cited in Balke, 311-312.

[35] Balke, 221.

[36] Balke, 97.

[37] Calvin says “The ground of controversy is this: our opponents hold that the land of Canaan was considered by the Israelites as supreme and final happiness, and now, since Christ was manifested, typifies to us the heavenly inheritance; whereas we maintain that, in the earthly possession which the Israelites enjoyed, they beheld, as in a mirror, the future inheritance which they believed to be reserved for them in heaven.” Institutes, 2.11.1

[38] Peter A. Lillback “Calvin’s Covenantal Response to the Anabaptist View of Baptism” The Failure of the American Baptist Culture, James B. Jordan, ed. (Geneva Divinity School, 1982), 221.

[39] ibid, 198.

[40] Institutes, 2.10.2. Johnson, 812 “While Calvin‟s exposition of the relationship between the Old and New Testaments in the Institutes is found largely in Book II (The Knowledge of God the Redeemer) rather than Book IV on the sacraments, one nonetheless observes that his treatment on Testamental unity first appeared at length in 1539, the same edition in which Calvin greatly expanded his defense of infant baptism. The two topics were integrally related”

[41] Institutes, 2.10.3

[42] Institutes, 2.10.3

[43] Institutes, 2.10.4

[44] Institutes, 2.10.7

[45] Institutes, 2.10.13

[46] A Work on the Proceedings of Pelagius, ch. 14.

[47] Institutes, 2.10.23

[48] Institutes, 2.11.3

[49] Institutes, 2.11.4

[50] Institutes, 2.11.4

[51] Institutes, 2.11.1

[52] A Treatise on the Spirit and the Letter, ch. 42

[53] Notice that Calvin here describes the ceremonies as accessories and appendages to the old covenant, the principal and body (substance?) of which is dead.

[54] Institutes, 2.11.7

[55] Institutes, 2.11.10

[56] Institutes, 2.11.7

[57] Institutes, 2.11.8

[58] Cf. Calvin’s commentary on Rom. 10:5 “The law has a twofold meaning; it sometimes includes the whole of what has been taught by Moses, and sometimes that part only which was peculiar to his ministration, which consisted of precepts, rewards, and punishments.”

[59] Institutes, 2.11.10

[60] Institutes, 2.11.7

[61] Institutes, 2.11.8

[62] Institutes, 2.7.1

[63] Compare with Witsius “Nor Formally the Covenant of Grace: Because that requires not only obedience, but also promises, and bestows strength to obey. For, thus the covenant of grace is made known, Jer. xxxii. 39. ‘and I will give them one heart, and one way, that they may fear me for ever.’ But such a promise appears not in the covenant made at mount Sinai. Nay; God, on this very account, distinguishes the new covenant of grace from the Sinaitic, Jer. xxxi. 31-33. And Moses loudly proclaims, Deut xxix. 4. ‘yet the Lord hath not given you a heart to perceive, and eyes to see, and ears to hear, unto this day.’ Certainly, the chosen from among Israel had obtained this. Yet not in virtue of this covenant, which stipulated obedience, but gave no power for it: but in virtue of the covenant of grace, which also belonged to them.” The Economy of the Covenants Between God and Man, (Phillipsburg, NJ: Presbyterian and Reformed), Vol. II, 187.

[64] Institutes, 2.11.8

[65] Compare with Bryan D. Estelle Leviticus 18:5 and Deuteronomy 30:1-14 in Biblical Theological Development: Entitlement to Heaven Foreclosed and Proffered (P & R Publishing, 2009), 128-130. “If one does not recognize this as a prophecy of the new covenant, then a host of unconvincing exegetical conclusions follow… Just as Leviticus 18:5 is taken up in later biblical allusions and echoes, so also is this Deuteronomy [30:6] passage. In Jeremiah 31:31-34, the language of the new covenant that was cloaked in the circumcision of heart metaphor is unveiled in this classic passage. I argued above that Deuteronomy 30:1-14 is a predictive prophecy of the new covenant, and, therefore, all that was implicit there becomes explicit in Jeremiah 31. In verse 31, Jeremiah says this will happen ‘in the coming days’ and in verse 33 he says ‘after these days’; both refer to the new covenant, messianic days.”

[66] Institutes, 2.10.7

[67]

[68] Moon, 114.

[69] In his commentary on Jeremiah 31, Calvin says “[T]he Fathers, who were formerly regenerated, obtained this favour through Christ, so that we may say, that it was as it were transferred to them from another source. The power then to penetrate into the heart was not inherent in the Law, but it was a benefit transferred to the Law from the Gospel…”

[70] Lillback, 218.

[71] Institutes, 2.11.9

[72] Calvin’s commentary on Hebrews 8:6.

[73] Commentary Heb. 8:10

[74] Commentary Heb. 8:10

[75] Commentary on Jer 31:33

[76] Moon, 119.

[77] Institutes, 2.11.10

[78] Institutes, 2.10.23

[79] A Work on the Proceedings of Pelagius ch. 13

[80] ibid, ch. 14-15.

[81] Institutes, 2.11.10

[82] Moon, 120.

[83] Calvin’s definition of “the Law’ in Institutes, 2.7.1

[84] “There is no doubt but that the Prophet includes the whole dispensation of Moses when he says, ‘I have made with you a covenant which you have not kept.’” Calvin’s commentary on Hebrews 8:8

[85] Chapter 7, Paragraphs 5 and 6.

[86] Allen C. Guelzo, “John Owen, Puritan Pacesetter”, Christianity Today, 20, No. 17 (May 21, 1976), 14.

[87] John Owen “An Exposition of the Epistle to the Hebrews: Hebrews 8:1-10:39” The Works of John Owen, vol. 22 (Johnstone & Hunter, 1855, ed. William H. Goold, “Books for the Ages” AGES Software, 2000), 84-89 (Heb. 8:6).

[88] Owen, 91-92 (Heb. 8:6).

[89] Owen, 92-93 (Heb. 8:6).

[90] Owen, 147 (Heb. 8:9).

[91] Owen, 103-104 (Heb. 8:6).

[92] Owen, 105 (Heb. 8:6).

[93] See Renihan, James M. Edification and Beauty: The Practical Ecclesiology of the English Particular Baptists, 1675-1705 (Milton Keynes: Paternoster, 2008). Hulse, Erroll. Who Are the Puritans?: And What Do They Teach? (Darlington, England: Evangelical Press, 2000), 188. Haykin, Michael A. G. Kiffin, Knollys and Keach: Rediscovering English Baptist Heritage (Leeds: Reformation Today, 1996). McGoldrick, James Edward. Baptist Successionism: A Crucial Question in Baptist History (Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow, 2000). Belyea, G. “Origins of the Particular Baptists.” Themelios. 32, no. 3 (2007): 40-67.

[94] Lavater, 353.

[95] Andrew Thomson, John Owen, Prince of Puritans, (Fern, Ross-shire, Great Britain: Christian Focus Publications, 1996), 54. Owen was referring to John Bunyan, whom he often went to hear preach.

[96] Crawford Gribben “John Owen, Baptism, and the Baptists” By Common Confession: Essays in Honor of James M. Renihan (Palmdale, CA: Reformed Baptist Academic Press, 2015).

[97] ibid.

[98] ibid.

[99] Nehemiah Coxe “A Discource of the Covenants that God made with men before the Law” Covenant Theology from Adam to Christ (Palmdale, CA: Reformed Baptist Academic Press, 2005), 30.

[100] For more information and a list of resources, see http://www.1689federalism.com

[101] see Moon.

[102] Woolsey, 37.

[103] “with regard to the holy fathers, it is to be observed, that though they lived under the Old Testament, they did not stop there, but always aspired to the New, and so entered into sure fellowship with it.” Institutes, 2.11.10

[104] Commentary Hebrews 8:10