In a recent post I summarized Scottish Presbyterian James Currie’s criticism of Bannerman/Westminster’s understanding of the visible/invisible church distinction. He quoted extensively from a 17th century French reformed theologian Jean Claude who had a famous debate (1678) with French Roman Catholic Bishop Jacques Bénigne Bossuet about the nature and authority of the church. I recently provided extensive quotes from that writing as well. Currie also commended “The True Idea of the Church, by Dr. Hodge of Princeton College, reprinted in Edinburgh some few years ago.”

In a recent post I summarized Scottish Presbyterian James Currie’s criticism of Bannerman/Westminster’s understanding of the visible/invisible church distinction. He quoted extensively from a 17th century French reformed theologian Jean Claude who had a famous debate (1678) with French Roman Catholic Bishop Jacques Bénigne Bossuet about the nature and authority of the church. I recently provided extensive quotes from that writing as well. Currie also commended “The True Idea of the Church, by Dr. Hodge of Princeton College, reprinted in Edinburgh some few years ago.”

Hodge’s essays on the church were written in the context of the American Presbyterian Church coming to grips with the implications of disestablishmentarianism. The result was nearly a century of debate over a variety of ecclesiological topics. In his lengthy dissertation, Peter J. Wallace (OPC) explains

The transformation in identity from “church” to “denomination” took time. The older understanding of the unity–or catholicity–of the visible church could not help but be eroded as “liberty of conscience” began to trump [visible] catholicity…

The Protestant Reformation did not reject the idea of catholicity. It simply claimed that the Pope was a usurper… At least through the seventeenth century, the principle of [visible] catholicity remained theoretically intact. The ideal was to have one orthodox church in any given region… It was in America that this older understanding of [visible] catholicity utterly disintegrated… The old idea of [visible] catholicity–one church per region–had broken down.

But American Protestants were not willing to surrender the idea of catholicity. When Roman Catholics accused them of being divided and divisive, Protestants replied that they were still united in doctrine and fellowship… If the older understanding of [visible] catholicity maintained a tenuous existence in the early nineteenth century (experiencing gradual erosions from the middle of the seventeenth century), the concept of conscience had been undergoing a revolution of its own. “Conscience” referred to an understanding of the right of the individual to decide what he or she believes on any given subject. The nineteenth century saw conscience gradually become a more central symbol than [visible] catholicity in defining religion and morals, resulting in the inward and outward fragmentation of Anglo-American Protestantism…

It was only in 1789 that Presbyterians revised their Confession of Faith to become the first Christian confession to make denominational pluralism an article of faith [23.3]… This new section, added in 1789, had the effect of altering the meaning of the Confession’s statement on the catholicity of the visible church (25.2-5), rendering the older concept of one church per region untenable.

Hodge’s work was reprinted in Scotland in support of the Free Church of Scotland split from the established church. Wallace notes “The Church of Scotland lost nearly half of its ministers to the Free Church Disruption of 1843, as 40% of the church departed in order to maintain the spiritual independence of the church against state interference.”

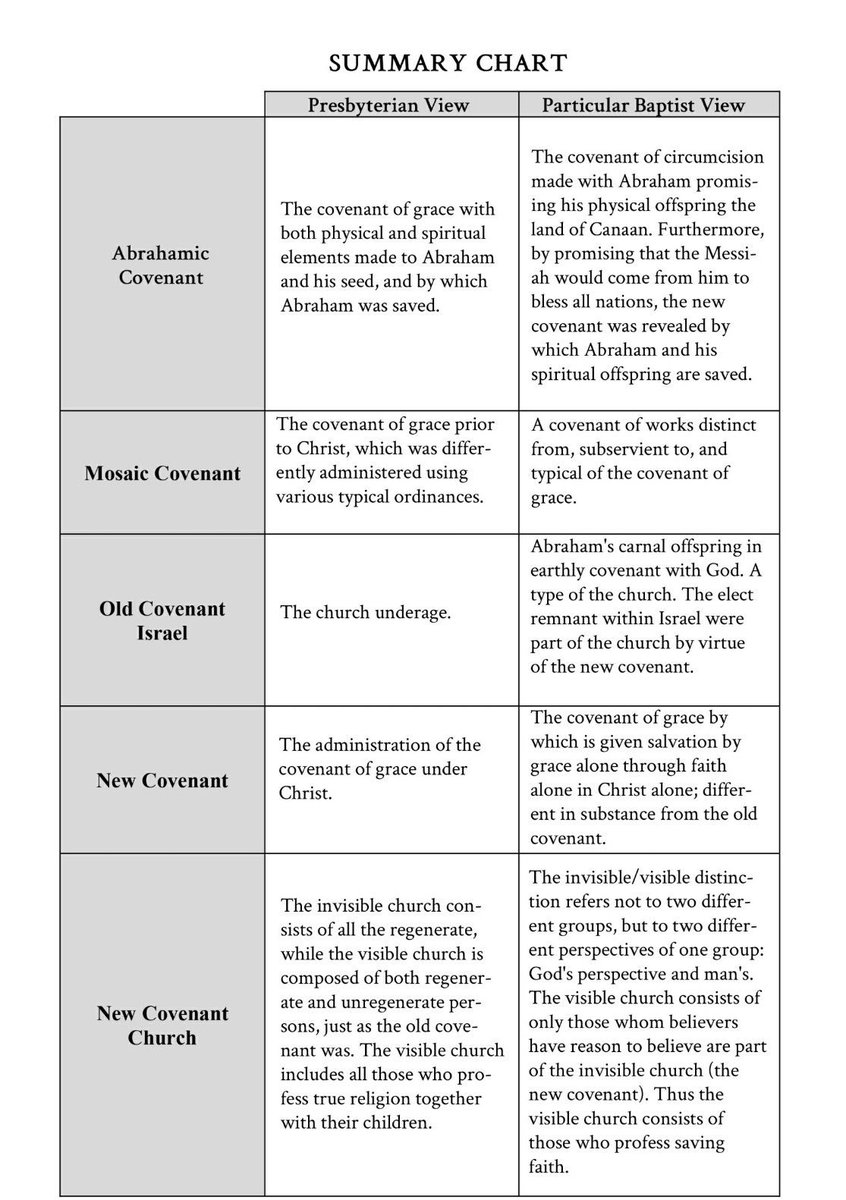

Our interest here is that Hodge’s understanding of the visible/invisible Church distinction is identical to the Reformed Baptist understanding – which is often dismissed offhand as an uninformed misunderstanding of Scripture simply because it differs from Westminster’s.

Like Jean Claude, Hodge sought to explain what is meant by “the communion of saints” in the Apostles’ Creed.

Not a Visible Organized Society

It is obvious that the Church, considered as the communion of saints, does not necessarily include the idea of a visible society organized under one definite form… [It] does not include the idea of any external organization. The bond of union may be spiritual… [The Apostles’ Creed] does not present it under the idea of an external society at all. (1-2)

Saints

The saints, therefore, according to the scriptural meaning of the term, are those who have been cleansed from guilt or justified, who have been inwardly renewed or sanctified, and who have been separated from the world and consecrated to God. Of such the Church consists. If a man is not justified, sanctified, and consecrated to God, he is not a saint, and therefore does not belong to the Church, which is the communion of saints. (2)

The True Idea of the Church

As to the bond by which the saints are united so as to become a Church, it cannot be anything external, because that may and always does unite those who are not saints… The proximate and essential bond of union between the saints, that which gives rise to their communion, and makes them the Church or body of Christ, is, therefore, the indwelling of the Holy Ghost. Such, then, is the true idea of the Church, or, what is the same thing, the idea of the true Church. It is the communion of saints, the body of those who are united to Christ by the indwelling of his Spirit. (2-3)

The only Church which is holy, which is one, which is catholic, apostolic, and perpetual, is the communion of saints, the company of faithful men, the mystical body of Christ, whose only essential bond of union is the indwelling of the Holy Ghost. That Spirit, however, always produces faith and love, so that all in whom he dwells are united in faith and Christian fellowship. (21)

The argument for the true doctrine concerning the Church, derived from the divine promises, is this. Those promises, according to the Scriptures, are made to the h umble, the penitent and believing; the Church, therefore, must consist exclusively of the regenerated. Those to whom the promises of divine presence, guidance, protection, and salvation, are made, cannot be a promiscuous multitude of all sorts of men. That theory of the Church, therefore, which makes it an external society, is necessarily destructive of religion and morality. (25)

It is conceded that the church is the body of Christ, and therefore consists of those who are in Christ; and as, according to the evangelical system, faith is the means of union with Christ, it follows, — l. That none but believers are in the church; and, 2. That all true believers are, as such, and for that reason alone, members of the church of Christ. 3. The church, therefore, in its true idea or essential nature, is not a visible society, but the company of faithful men, – the coetus sanctorum, or the communion of saints. The turning point, therefore, between the two systems, — that on which all other matters in dispute between ritualists and the evangelical, Romanists and Protestants, depend,—is the answer to the question, What unites us to Christ? If we are united to Christ by faith, then all believers are in Christ, and constitute the church. (32)

The Meaning of Ekklesia

The word ἐκκλησίαν from ἐκκλησία, evocare, means an assembly or body of men evoked, or called out and together. It was used to designate the public assembly of the people among the Greeks, collected for the transaction of business. It is applied to the tumultuous assembly called together in Ephesus by the outcries of Demetrius, Acts six. 39. It is used for those who are called out of the world, by the gospel, so as to form a distinct class… [I]t is not those who merely hear the call of the gospel, who constitute the Church, but those who obey the call… In all the various applications, therefore, of the word ἐκκλησίαν in the New Testament, we find it uniformly used as a collective term for the [GREEK]xXiivoi or [GREEK]tdexTot, that is, for those who obey the gospel call, and who are thus selected and separated, as a distinct class from the rest of the world. (4)

The word in the New Testament is never used except in reference to the company of true believers. This consideration alone is sufficient to determine the nature of the Church. (6)

Synonyms of Ekklesia

Those epistles in the New Testament which are addressed to Churches, are addressed to believers, saints, the children of God… From this collation it appears, that to call any body of men a Church, is to call them saints, sanctified in Christ Jesus, elected to obedience and sprinkling of the blood of Christ, partakers of the same precious faith with the apostles, the beloved of God, and faithful brethren. The inference from this fact is inevitable. The Church consists of those to whom these terms are applicable… From all this, it is evident that the terms, believers, saints, children of God, the sanctified, the justified, and the like, are equivalent to the collective term Church, so that any company of men addressed as a Church, are always addressed as saints, faithful brethren, partakers of the Holy Ghost, and children of God. The Church, therefore, consists exclusively of such. (7-9)

It is to degrade and destroy the gospel to apply this description of the Church as the body of Christ, to the mass of nominal Christians, the visible Church, which consists of “all sorts of men.” No such visible society is animated by his Spirit, is a partaker of his life, and heir of his glory. It is to obliterate the distinction between holiness and sin, between the Church and the world, between the children of God and the children of the devil, to apply what the Bible says of the body of Christ to any promiscuous society of saints and sinners. (10)

The Church is declared to be the temple of God… the family of God… the flock of Christ… the bride of Christ… These descriptions of the Church are inapplicable to any external visible society as such; to the Church of Rome, the Church of England, or the Presbyterian Church. The only Church of which these things are true, is the communion of saints, the body of true Christians.

Holiness

If then we conceive of the Church as the communion of saints, as the body of Christ, in which the Holy Spirit dwells as the source of its life, we see that the Church is and must be holy. It must be inwardly pure, that is, its members must be regenerated men, and it must be really separated from the world, and consecrated to God. These are the two ideas included in the scriptural sense of holiness, and in both these senses the Church is truly holy. But in neither sense can holiness be predicated of any external visible society as such. No such society is really pure, nor is it really separated from the world, and devoted to God. This is evident from the most superficial observation. It is plain that neither the Roman, the Greek, the English, nor the Presbyterian Church, falls within the definition of the Church as the coetus sanctorum, or company of believers. (12)

The holiness attributed to the church in Scripture, includes inward purity and outward consecration to God. In neither of these senses can holiness be predicated of any who are not true believers. (57)

Union with Christ

The church, as is conceded, consists of those who are in Christ. Whatever, therefore, is the condition of union with Christ, is the condition of membership in the church. (58)

They Are All Taught of God

The Church, considered as the communion of saints, is one in faith. The Spirit of God leads his people into all truth. He takes of the things of Christ and shows them unto them. They are all taught of God [Is 54:13; Jer 31:31; Jn 6:45]. The anointing which they have received abideth with them, and teacheth them all things, and is truth. 1 John ii. 27. Under this teaching of the Spirit, which is promised to all believers, and which is with and by the word, they are all led to the knowledge and belief of all necessary truth. (15)

The Visible Church

if the Church is the coetus sanctorum, the company of believers; if it is the body of Christ, and if his body consists of those, and of those only, in whom he dwells by his Spirit, then the Church is visible only, in the sense in which believers are visible… Wherever there are true believers, there is the true Church; and wherever such believers confess their faith, and illustrate it by a holy life, there the Church is visible. The Church is visible, because believers are, by their “effectual calling,” separated from the world. Though in it, they are not of it…

This becomes intelligible by adverting to the origin of the Christian community. The admitted facts in reference to this subject are — 1. That our Lord appeared on earth as the Son of God, and the Saviour of sinners. To all who received him he gave power to become the sons of God; they were justified and made partakers of the Holy Ghost, and thereby united to Christ as living members of his body. They were thus distinguished inwardly and outwardly from all other men. 2. He commissioned his disciples to go into all the world and preach the gospel to every creature. He enjoined upon them to require as the conditions of any man’s being admitted into their communion as a member of his body, repentance toward God, and faith in our Lord Jesus Christ. 3. He commanded all who did thus repent and believe, to unite together for his worship, for instruction, for the administration of the sacraments, and for mutual watch and care. For this purpose he provided for the appointment of certain officers, and gave, through his apostles, a body of laws for their government, and for the regulation of all things which those who believed were required to perform. Provision was thus made, by divine authority, for the Church assuming the form of an external visible society…

If, then, the Church is the body of Christ; if a man becomes a member of that body by faith; if multitudes of those who profess in baptism the true religion, are not believers, then it is just as certain that the external body consisting of the baptized is not the Church, as that a man’s calling himself a Christian does not make him a Christian. (65-68)

In his [the Apostle John’s] day many who had been baptized, and received into the communion of the external society of Christians, were not true believers. How were they regarded by the apostle? Did their external profession make them members of the true Church, to which the promises pertain? St. John answers this question by saying, “They went out from us, but they were not of us; for if they had been of us, they would no doubt have continued with us : but they went out, that it might be made manifest that they were not all of us. But ye have an unction from the Holy One, and ye know all things.” 1 John ii. 19, 20. It is here taught, 1. That many are included in the pale of the external Church, who are not members of the true Church. 2. That those only who have an unction of the Holy One, leading them into the knowledge of the truth, constitute the Church. 3. And consequently the visibility of the Church is that which belongs to the body of true believers. (70)

Everything comes back to the question. What is the Church? True believers constitute the true Church; professed believers constitute the outward Church. These two things are not to be confounded. The external body is not, as such, the body of Christ. Neither are they to be separated as two Churches; the one true and the other false, the one real and the other nominal. They differ as the sincere and insincere differ in any community… The question, how far the outward Church is the true Church, is easily answered. Just so far as it is what it professes to be, and no further. So far as it is a company of faithful men, animated and controlled by the Holy Spirit, it is a true Church, a constituent member of the body of Christ. If it be asked further, how we are to know whether a given society is to be regarded as a Church; we answer, precisely as we know whether a given individual is to be regarded as a Christian, i. e. by their profession and conduct. (72-73)

Regeneration Goggles?

[Objection:] “[W]here was there any such society, answering to the Protestant definition, before the Reformation?” This objection rests upon the misconception which Ritualists do not appear able to rid themselves of. When Protestants say the Church is invisible, they only mean that an inward and consequently invisible state of mind is the condition of membership, and not that those who have this internal qualification are invisible, or that they cannot be so known as to enable us to discharge the duties which we owe them. When asked, what makes a man a Christian? we say, true faith. When asked whom must we regard and treat as Christians? we answer, those who make a credible profession of their faith. Is there any contradiction in this? Is there any force in the objection, that if faith is an inward quality, it cannot be proved by outward evidence? Thus, when Protestants are asked, what is the true Church? they answer, the company of believers. When asked what associations are to be regarded and treated as churches? they answer, those in which the gospel is preached. When asked further, where was the Church before the Reformation? they answer, just where it was in the days of Elias, when it consisted of a few thousand scattered believers. (73)

The General Call a Call to Bare Profession?

The nature of the Church, therefore, must depend on the nature of the gospel call. If that call is merely or essentially to the outward profession of certain doctrines, or to baptism, or to anything external, then the Church must consist of all who make that profession, or are baptized. But if the call of the gospel is to repentance toward God, and faith in our Lord Jesus Christ, then none obey that call but those who repent and believe, and the Church must consist of penitent believers. It cannot require proof that the call of the gospel is to faith and repentance…

Every [GREEK],xxXt,trta is composed of the [GREEK]xXtjtoi, of those called out and assembled. But the word [GREEK]xXrjTot, as applied to Christians, is never used in the New Testament, except in reference to true believers. If, therefore, the Church consists of “the called,” it must consist of true believers. (5-6)

The faith which has all this power is not a mere historical assent to the gospel, but a cordial acquiescence in its truths, founded on the testimony of God, with and by the truth through his Spirit. From these considerations it is abundantly evident that none are in Christ but true believers; and as it is conceded that the church consists of those who are in Christ, it must consist of true believers. (33)

Visible Church Includes Hypocrites?

To this argument it is indeed objected, that as the apostles addressed all the Christians of Antioch, Corinth, or Ephesus, as constituting the Church in those cities, and as among them there were many hypocrites, therefore the word Church designates a body of professors, whether sincere or insincere. The fact is admitted, that all the professors of the true religion in Corinth, without reference to their character, are called the church of Corinth. This, however, is no answer to the preceding argument. It determines nothing as to the nature of the Church. It does not prove it to be an external society, composed of sincere and insincere professors of the true religion. All the professors in Corinth are called saints, sanctified in Christ Jesus, the saved, the children of God, the faithful believers, &c., &c. Does this prove that there are good and bad saints, holy and unholy sanctified persons, believing and unbelieving believers, or men who are at the same time children of God and children of the devil? Their being called believers does not prove that they were all believers; neither does their being called the Church prove that they were all members of the Church. They are designated according to their profession. In professing to be members of the Church, they professed to be believers, to be saints and faithful brethren, and this proves that the Church consists of true believers…

In the same sense and in no other, in which infidels may be called believers, and wicked men saints, in the same sense may they be said to be included in the Church. If they are not really believers, they are not the Church. They are not constituent members of the company of believers. (7)

It is not to be inferred from the fact that all the members of the Christian societies in Rome, Corinth, and Ephesus, are addressed as believers, that they all had true faith. But we can infer, that since what is said of them is said of them as believers, it had no application to those who were without faith. In like manner, though all are addressed as belonging to the Church, what is said of the Church had no application to those who were not really its members. Addressing a body of professed believers, as believers, does not prove them to be all sincere; neither does addressing a body of men as a Church, prove that they all belong to the Church. In both cases they are addressed according to their profession. If it is a fatal error to transfer what is said in Scripture of believers, to mere professors, to apply to nominal what is said of true Christians, it is no less fatal to apply what is said of the Church to those who are only by profession its members. It is no more proper to infer that the Church consists of the promiscuous multitude of sincere and insincere professors of the true faith, from the fact that all the professors, good and bad, in Corinth, are called the Church, than it would be to infer that they were all saints and children of God, because they are all so denominated. It is enough to determine the true nature of the Church, that none are ever addressed as its members, who are not, at the same time, addressed as true saints and sincere believers. (9)

Of the objections commonly urged against the doctrine that the church is the communion of saints, consisting of true believers, those only which demand notice in this connexion are,—First, that as the societies at Ephesus, Corinth, and Rome were undoubtedly churches, and as they were composed of insincere as well as sincere professors of faith, it follows that the church does not consist exclusively of true believers. This objection has already been answered. The fact referred to proves only that those who profess to be members of the church are addressed and treated as members. In the same manner, those who professed to be believers, saints, the children of God, are constantly in Scripture addressed as being what they professed to be. If, therefore, addressing a body of men as a church proves that they are really its constituent members, addressing them as believers and saints must prove they all have true faith, and are really holy. The objection, therefore, is founded on a false assumption, viz., that men are always what they are addressed as being; and it would prove far more than the objector is willing to admit, viz., that all the members of the external church are saints and believers, and would thus establish the very doctrine the objection is adduced to refute. (61-62)

The Parables of the Kingdom

A second and more plausible objection is founded upon those parables of our Lord in which the kingdom of heaven is compared to a net containing fish, good and bad, and to a field in which tares grow together with the wheat. As the church and kingdom of heaven are assumed to be the same, it is inferred that if the one includes good and bad, so must also the other.

In answer to this objection it may be remarked, in the first place, that it is founded on a false assumption. The terms, “kingdom of God” and “ church,” are not equivalent. Many things are said of the one which cannot be said of the other. It cannot be said of the church that it consists not in meat and drink, but in righteousness, and peace, and joy in the Holy Ghost. Nor can it be said that the church is within us; neither are we commanded to seek first the church; nor is the church said to be at hand. All these forms of expression occur in reference to the kingdom of God, but are inapplicable to the church. It is evident, therefore, that it is not safe to conclude that something is true of the church, simply because it is a parcel of the kingdom of God…

[T]he parables in question were not intended to teach us the condition of membership in the kingdom of heaven, they cannot decide that point. In one place Christ asserts didactically, that regeneration by the Holy Spirit is essential to admission into his kingdom; shall we infer, in direct opposition to this assertion, that his kingdom includes both the regenerate and unregenerate, because he compares it to a net containing fishes, good and bad? Certainly not, because the comparison was not designed to teach us what is the condition of membership in his kingdom. This, however, is the precise point in dispute. What is the church? What is the condition of membership in the body of Christ? Does his body consist of all the baptized, or of all true believers ? As our Lord did not intend to answer these questions in those parables, they do not answer them. The design of each particular parable is to be learned from the occasion on which it was delivered, and from its contents. That respecting the tares and the wheat was evidently intended to teach, that as God has not given us the power to inspect the heart, or to discriminate between the sincere and insincere professors of religion, he has not imposed on us the obligation to do so. That is his work. We must allow both to grow on together until the harvest, when he will effect the separation. This surely does not teach that what the Scriptures say of the wheat is to be understood of the tares. Others of these parables are obviously designed to teach, that external profession or relations cannot secure the blessings of the kingdom of God. It is not every one who says, Lord, Lord, who is to be admitted into his presence. These parables teach that many of those who profess to be the disciples, and who, in the eyes of men, constitute his kingdom, are none of his. This is a very important lesson; but if we were to infer, from the figure in which it is inculcated, that mere profession does make men members of Christ’s kingdom, we should infer the very opposite from what he intended to teach. To learn the condition of membership in that kingdom, we must turn to those passages which are designed to teach us that point, —-to those which professedly set forth the nature of that kingdom, and the terms of admission into it.

This suggests a third remark in answer to the above objection. Whenever the kingdom of God means the same thing as the church, it is expressly taught that admission into it depends on saving faith, or an inward spiritual change, and not on external rites or profession. The ancient prophets having predicted, that after the rise and fall of other kingdoms the God of heaven would set up a kingdom, the establishment of that kingdom became to his ancient people an object of expectation and desire. They were, however, greatly mistaken both as to its nature and the terms of admission into it. They had much the same notion of the kingdom of God that ritualists now have of the church. They expected it to be, in its essential character, an external organization, and the condition of membership to be descent from Abraham, or the rite of circumcision. Our Lord did not simply modify this conception by teaching that his kingdom, instead of being a visible organization with kings and nobles, was to be such an organization with cardinals and bishops; and that, instead of circumcision, baptism was to secure membership. He presented a radically different idea of its whole nature. He taught that it was to be a spiritual kingdom,—that it was to have its seat in the heart,—its Sovereign being the invisible God in Christ,—its laws such as relate to the conscience,—-its service the obedience of faith,—its rewards eternal life. It is true, he imposed upon his people the duty of confession, and other obligations which implied their manifestation to the world, and their external union among themselves. But these are mere incidents. His kingdom no more consists in these externals than the nature of man in his name or colour. The kingdom of Christ is therefore spiritual, not only as opposed to secular, but as distinguished from external organization. Such organization is not the church…

The question, which kingdom a man belongs to, the kingdom of Christ or the kingdom of Satan, the church or the world, does not depend on anything external, but on the state of his heart. It is a contradiction to say that the kingdom of Satan consists of good and bad, of the renewed and the unrenewed. It is no less a contradiction to say that the kingdom of Christ consists of the wicked and the good, the sincere and the insincere. The very idea of the one kingdom is, that it consists of those who obey Satan, and that of the other, that it is composed of those who obey Christ. If it is a contradiction to say there are good wicked men, it is no less a contradiction to say there are wicked good men. If Satan’s kingdom consists of the wicked, Christ’s kingdom consists of the good. Accordingly, whenever our Lord states the condition of admission into his kingdom, he declares it to be a change of heart, without which, he says, it is impossible any should enter it : “ Verily, verily, I say unto thee, Except a man be born again, he cannot see the kingdom of God. Except a man be born of water and of the Spirit, he cannot enter the kingdom of God. That which is born of the flesh is flesh; and that which is born of the Spirit is spirit. Marvel not that I said unto you, Ye must be born again.” Whatever else this passage teaches, it certainly asserts the absolute necessity of an inward spiritual birth in order to membership in Christ’s kingdom. (62-64)

Outside of the Church There is No Salvation

Cyprian is urged as another authority, who says: “Whosoever, divorced from the Church, is united to an adulteress, is separated from the Church’s promises; nor shall that man attain the rewards of Christ, who relinquishes his Church. He is a stranger, he is profane, he is an enemy.” All this is undoubtedly true. It is true, as Augustin says, that the good cannot divide themselves from the Church; it is true, as Irenaeus says, where the Church is, there the Spirit of God is; and where the Spirit is, there the Church is. This is the favorite motto of Protestants. It is also true, as Cyprian says, that he who is separated from the Church, is separated from Christ. This brings the nature of the Church down to a palpable matter of fact…

To say, therefore, with Augustin, that no good man can leave the Church, is only to say that the good will love and cleave to each other; to say, with Irenaeus, that where the Spirit of God is, there is the Church, is to say the presence of the Spirit makes the Church; and to say with Cyprian, that he who is separated from the Church, is separated from Christ, is only saying, that if a man love not his brother whom he hath seen, he cannot love God whom he hath not seen. If the Church is the communion of saints, it includes all saints; it has catholic unity because it embraces all the children of God. And to say there is no salvation out of the Church, in this sense of the word, is only saying there is no salvation for the wicked, for the unrenewed and unsanctified… Wherever the Spirit of God is, there the Church is; and as the Spirit is not only within, but without all external Church organizations, so the Church itself cannot be limited to any visible society. (19-20)

Visible Church Succession from Apostles?

If, on the other hand, the Church is a company of believers, if it is the communion of saints, all that is essential to its perpetuity is that there should always be believers. It is not necessary that they should be externally organized, much less is it necessary that they should be organized in any prescribed form. It is not necessary that any line of officers should be uninterruptedly continued; much less is it necessary that those officers should be prelates or popes… But the Church can exist without a pope, without prelates, yea, without presbyters, if in its essential nature it is the communion of saints. There is, therefore, no promise of an uninterrupted succession of validly ordained church-officers, and consequently no foundation for faith in any such succession. In the absence of any such promise, the historical argument against “apostolic succession,” becomes overwhelming and unanswerable. (20-21)

Not of This World

We find in the Scriptures frequent assurances that the Church is to extend from sea to sea, from the rising to the setting of the sun; that all nations and people are to flow unto it. These promises the Jews referred to their theocracy. Jerusalem was to be the capital of the world; the King of Zion was to be the King of the whole earth, and all nations were to be subject to the Jews. Judaizing Christians interpret these same predictions as securing the universal prevalence of the theocratic Church, with its pope or prelates. In opposition to both, the Redeemer said: “My kingdom is not of this world.” His apostles also taught that the kingdom of God consists in righteousness, peace, and joy in the Holy Ghost. The extension of the Church, therefore, consists in the prevalence of love to God and man, of the worship and service of the Lord Jesus Christ. It matters not how the saints may be associated; it is not their association, but their faith and love that makes them the Church, and as they multiply and spread, so does the Church extend. All the fond anticipations of the Jews, founded on a false interpretation of the divine promises, were dissipated by the advent of a Messiah whose kingdom is not of this world. History is not less effectually refuting the ritual theory of the Church, by showing that piety, the worship and obedience of Christ, the true kingdom of God, is extending far beyond the limits which that theory would assign to the dominion of the Redeemer. (24)

The men of the world are devoted to the world,——they do not belong to the peculiar people whom God has called out of the world and set apart for himself. (57)

National Churches are of the World

And no more wicked or more disastrous mistake has ever been made, than to transfer to the visible society of professors of the true religion, subject to bishops having succession, the promises and prerogatives of the body of Christ. It is to attribute to the world the attributes of the Church; to the kingdom of darkness the prerogatives of the kingdom of light. It is to ascribe to wickedness the character and blessedness of goodness. Every such historical Church has been the world baptized; all the men of a generation, or of a nation, are included in the pale of such a communion. If they are the Church, who are the world? If they are the kingdom of light, who constitute the kingdom of darkness? To teach that the promises and prerogatives of the Church belong to these visible societies, is to teach that they belong to the world, organized under a particular form and called by a new name. (29)

Individuals, Not Societies or Nations, Redeemed

[H]oliness and salvation are promised to every member of the Church. This is obvious; 1. Because these are blessings of which individuals alone are susceptible. It is not a community or society, as such, that is redeemed, regenerated, sanctified, and saved. Persons, and not communities, are the subjects of these blessings[.] (24)

The Right of Private Judgment

[A]ccording to the Scriptures, it is the duty of every Christian to try the spirits whether they be of God, to reject an apostle, or an angel from heaven, should he deny the faith, and of that denial such Christian is of necessity the judge. Faith, moreover, is an act for which every man is personally responsible; his salvation depends upon his believing the truth. He must, therefore, have the right to believe God, let the chief officers of the Church teach what they may. The right of private judgment is, therefore, a divine right. It is incompatible with the ritual theory of the Church, but perfectly consistent with the Protestant doctrine that the Church is the communion of saints. (29)

National Israel the Church?

Under the old dispensation, the whole nation of the Hebrews was called holy, as separated from the idolatrous nations around them, and consecrated to God. The Israelites were also called the children of God, as the recipients of his peculiar favours. These expressions had reference rather to external relations and privileges than to internal character. In the New Testament, however, they are applied only to the true people of God. None are there called saints but the sanctified in Christ Jesus. None are called the children of God, but those born of the Spirit, who being children are heirs, heirs of God, and joint heirs with Jesus Christ of a heavenly inheritance. When, therefore, it is said that the Church consists of saints, the meaning is not that it consists of all who are externally consecrated to God, irrespective of their moral character, but that it consists of true Christians or sincere believers. (2)

Much the most plausible argument of Romanists is derived from the analogy of the old dispensation. That the Church is a visible society, consisting of the professors of the true religion, as distinguished from the body of true believers, known only to God, is plain, they say, because under the old dispensation it was such a society, embracing all the descendants of Abraham who professed the true religion, and received the sign of circumcision… If such a society existed then by divine appointment, what has become of it? Has it ceased to exist? Has removing its restriction to one people destroyed its nature? Does lopping certain branches from the tree destroy the tree itself? Far from it. The Church exists as an external society now as it did then; what once belonged to the commonwealth of Israel, now belongs to the visible Church… Such is the favourite argument of Romanists; and such, (striking out illogically the last clause, which requires subjection to prelates, or the Pope,) we are sorry to say is the argument of some Protestants, and even of some Presbyterians.

The fallacy of the whole argument lies in its false assumption, that the external Israel was the true Church. It was not the body of Christ; it was not pervaded by his Spirit. Membership in it did not constitute membership in the body of Christ. The rejection or destruction of the external Israel was not the destruction of the Church. The apostasy of the former was not the apostasy of the latter. The attributes, promises, and prerogatives of the one, were not those of the other. In short, they were not the same…

It is to be remembered that there were two covenants made with Abraham. By the one, his natural descendants through Isaac were constituted a commonwealth, an external, visible community. By the other, his spiritual descendants were constituted a Church. The parties to the former covenant were God and the nation; to the other, God and his true people. The promises of the national covenant were national blessings; the promises of the spiritual covenant, (i. e. of the covenant of grace,) were spiritual blessings, reconciliation, holiness, and eternal life. The conditions of the one covenant were circumcision and obedience to the law; the condition of the latter was, is, and ever has been, faith in the Messiah as the seed of the woman, the Son of God, the Saviour of the world. There cannot be a greater mistake than to confound the national covenant with the covenant of grace, and the commonwealth founded on the one with the Church founded on the other.

When Christ came “the commonwealth” was abolished, and there was nothing put in its place. The Church remained. There was no external covenant, nor promises of external blessings, on condition of external rites and subjection. There was a spiritual society with spiritual promises, on the condition of faith in Christ. In no part of the New Testament is any other condition of membership in the Church prescribed than that contained in the answer of Philip to the eunuch who desired baptism: “If thou believest with all thine heart, thou mayest. And he answered and said, I believe that Jesus Christ is the Son of God.” — Acts viii. 37. The Church, therefore, is, in its essential nature, a company of believers, and not an external society, requiring merely external profession as the condition of membership. While this is true and vitally important, it is no less true that believers make themselves visible by the profession of the truth, by holiness of life, by separation from the world as a peculiar people, and by organizing themselves for the worship of Christ, and for mutual watch and care. (74-75)

Augustine

Augustine says, the Church is a living body, in which there are both a soul and body. Some are members of the Church in both respects, being united to Christ, as well externally as internally. These are the living members of the Church; others are of the soul, but not of the body — that is, they have faith and love, without external communion with the Church. Others, again, are of the body and not of the soul — that is, they have no true faith. These last, he says, are as the hairs, or nails, or evil humours of the human body. According to Augustin, then, the wicked are not true members of the Church; their relation to it is altogether external. They no more make up the Church, than the scurf or hair on the surface of the skin make up the human body. This representation is in entire accordance with the Protestant doctrine, that the Church is a communion of saints, and that none but the holy are its true members. It expressly contradicts the Romish and Oxford theory, that the Church consists of all sorts of men; and that the baptized, no matter what their character, if they submit to their legitimate pastors, are by divine right constituent portions of the Church; and that none who do not receive the sacraments, and who are not thus subject, can be members of the body of Christ. (14-15)

History of the Decline of the True Idea of the Church

The history of the idea of the church would be one of the most interesting chapters of a history of doctrine. Such a history would naturally divide itself into the following periods: —1. The apostolic period; 2. The transition period, during which the attributes of the true church came to be gradually transferred to the external society of professed believers; 3. The period of the complete ascendency of the ritual theory of the church; and, 4. The Reformation period…

We have seen that, during the apostolic period, the church was regarded as a company of faithful men, a coetus sanctorum, or body of saints, and that true faith was the indispensable condition of membership, so that none but believers were considered to belong to the church, and all believers were regarded as within its pale. The very word [GREEK]e’xxqurla, during this period, was never used except as a collective term for the [GREEK]Kltn-roi, for those whom God, by his Word and Spirit, had called out of the world or kingdom of Satan, into the kingdom of his dear Son. None, therefore, were ever addressed as members of the church, who were not also called believers, saints, the sanctified in Christ Jesus, the children of God, and heirs of eternal life. They were all described as members of the body of Christ, in whom he dwells by his Spirit, and who, therefore, are the temple of God. They constitute the family of God, the flock of the good Shepherd, and the bride of Christ… Believers, therefore, are Abraham’s seed, and heirs according to the promise. They, and they alone, constitute that body of which all these attributes are predicated, and to which all these promises are made. Such being the nature of the church, as it is described in the apostolic writings, it follows, of course, that all out of the church perish, and all within the church are saved…

The transition period cannot be marked off by precise limits… One is soon perplexed when he endeavours to reduce the declarations of the fathers of this period to any consistent theory… By the common consent of Christians, the church is one, catholic, holy, and apostolical. We find, therefore, these attributes, in all their modifications, freely ascribed to the church by the fathers of the first three centuries. By the church, however, they often meant the aggregate of believers. This is the true idea of the church. In this sense all the attributes above mentioned do truly belong to it. But as believers actually and visibly exist in this world, as they manifest themselves to be believers by the profession of their faith, by their union in the worship of Christ, and by their holy life in obedience to his commands, the body of those who professed to be believers was called the church. To the aggregate, then, of these professors of the true faith, all the attributes of the church were referred. This was a very natural process, and had the semblance of scriptural authority in its behalf. In the Bible all who profess to believe, are called believers, and every thing that is or can be predicated of believers is predicated of such professors. From this, however, it is not to be inferred that the attributes of believers belong to unbelievers. The only thing this scriptural usage teaches us is, that the church consists of believers, and that all that is predicated of the church is ascribed to it as so constituted. The fathers, however, went one step beyond the usage of Scripture. They not merely addressed professed believers as believers, and spoke of the aggregate of such professors as the church, but they transferred to the body of professors the attributes which belonged to the body of believers. Even this was in their day a much more venial error than it is in ours. For the great body of professors were at first, and especially in times of persecution, sincere believers; and the distinction between the visible church and the world was then the distinction between Christianity and heathenism. It was natural, therefore, to speak of this band of united and suffering Christians, separated from their idolatrous countrymen, as indeed the church of which unity, catholicity, and holiness could be predicated, and out of whose pale there is no salvation. It is also to be remembered, that it was mainly in opposition to heretics that the fathers claimed for the body of professors the attributes of the true church. They could say, with full propriety, that out of the pale of the visible church there is no salvation, because out of that pale there was then no saving truth. All were in the visible church except the heathen and heretics who denied all of Christianity but its name. The church, therefore, in the sense of these early fathers, included all who professed faith in the true gospel; and, therefore, their claiming for such professors the attributes of the true church, is something very different from the conduct of those who in our day set up that claim in behalf of a small portion of the professed followers of Christ…

In experience, however, it was found that multitudes were members of the church who were not members of Christ, and who were entirely destitute of his Spirit… There were three methods of meeting this difficulty, all of which were adopted:—

1. A distinction was made between the visible church and the true church… It was, therefore, denied that the attributes and promises belonging to the church pertained to any but the living members of Christ’s body. This is the true doctrine, and differs in no essential particular from the doctrine afterwards revived at the Reformation, and universally adopted by Protestants. It was substantially their distinction between the visible and invisible church. This was the method adopted by Origen, and afterwards by Augustin… Only the holy really belong to the church; the wicked are in it only in appearance… The saints are the wheat, the wicked are the chaff ; the latter are no more the church than chaff is wheat… To Augustin the same objection was made by the Donatists that is now made by Romanists against Protestants, viz., that the distinction between the church visible and invisible supposes there are two churches. He answered the objection, just as Protestants do, by saying there is but one church; the wicked are not in the church; that the distinction between sincere and insincere Christians does not suppose there are two gospels and two Christs. It is one and the same church that appears on earth, with many impenitent men attached to it in external communion, which in heaven is to appear in its true character…

2. A second method adopted to reconcile the actual with the ideal church, the visible with the invisible, was the exercise of discipline…

3. A third method of getting over the difficulty was unhappily adopted and sanctioned. The whole theory of the church was altered and corrupted. It was assumed that all the attributes of the church belonged to the visible society of professed Christians. It was, however, apparent that such society did not possess these attributes according to the scriptural account of their nature. The view taken, therefore, of the nature of these attributes was changed…

The Bible says there is no salvation out of the church, for the church includes all the saints. The early fathers said there was no salvation out of the church, for there were none out of the church but heathen and heretics. It was a very different matter, however, when Cyprian came to deny salvation to his brethren holding the same faith, and giving the same evidence of being in Christ with himself. To them he says there is no salvation, because they were not in communion with the right bishop… Thus the whole theory and nature of the church was changed… This was the perversion of the true doctrine effected by Cyprian… This was the parent corruption, the fruitful source of almost all the other evils which have afflicted the church…

It is plain, from this brief survey, that the theory concerning the church passed, during the first few centuries, through these several stages. The apostles represented it as consisting of true believers; many of the fathers considered it as including all the professors of the true religion, as distinguished from Jews, pagans, and heretics; and then it came to be regarded as consisting of those professors of the true religion who were subject to bishops having succession; and to such society of professors all the attributes, promises, and prerogatives belonging to the true church were referred. As, however, it was seen that such attributes did not, in fact, belong to the society of professed believers, some made the distinction between the visible and invisible church, referring these attributes and promises only to the latter; others endeavoured to make the one identical with the other; and others perverted the nature of these attributes to make them answer to their preconceived conception of the church…

At first the unity of the church was made to rest on the indwelling of the Spirit, producing unity of faith and fellowship. Next, it was conceived of as belonging to the external body of professors, as distinguished from infidels and heretics. But when orthodox men separated from this external society, Cyprian asserted they were not of the church. Why not? They had the same faith, the same sacraments, and the same discipline or polity, but they were not subject to legitimate bishops. Soon, however, apostolic bishops separated. What was to be said now? Some other external bond of unity than the episcopate became essential, if the external unity of the church was to be preserved. For the very same reason, and with quite as much show of right, as Cyprian said no man was in the church who was not subject to a regularly consecrated bishop, did Gregory say, No bishop was in the church who is not subject to the Pope. The papal monarchy of the middle ages was, therefore, the natural product of Cyprian’s theory of the church…

Against this system the Reformation was a protest. The Reformers protested, first, against the fundamental error of the whole theory, viz., that the visible church is, in such a sense, the true church; that the attributes, promises, and prerogatives pertaining to the latter, belong to the former. In opposition to this doctrine, they maintained that the church consists of true believers; that it is a company of faithful men, a communion of saints, to which no man belongs who is not a true child of God… This is the essential character of the protest entered by all the churches of the Reformation. In proof of this, it will be sufficient to advert briefly to the teachings of those churches, in their symbolical books, as to the nature of the church.

Reformation Confessions

The Lutheran Church was the oldest daughter of the Reformation, and on this subject her standards are very explicit. Augs. Con., § vii.: “The church is a congregation of saints, in which the gospel is properly taught, and the sacraments rightly administered. And to the true unity of the church, agreement in the doctrine of the gospel and the administration of the sacraments is sufficient.” § viii.: “Although the church is, properly, a congregation of saints and of true believers, yet as in this life many hypocrites and wicked persons are included, it is lawful to use the sacraments administered by wicked men.”

The fourth head of the apology of the Augsburg Confession is a defence of the definition of the church as the congregation of saints. After saying and proving that it was so defined in Scripture, it refers to the language of the Creed, “which requires us to believe that there is a holy catholic church.” But the wicked are not the church. And the next clause, “communion of saints,” is added to explain what the church is,—viz., “the congregation of saints, having fellowship in the same gospel or doctrine, and in the same Holy Spirit, who renews, sanctifies, and governs their hearts.”

Again: “Although, therefore, hypocrites and evil men are connected with the church by external rites, yet, when the church is defined, it is necessary to describe it as the true body of Christ, that which is in name and reality the church.” “If the church, which is the true kingdom of Christ, is distinguished from the kingdom of the devil, it is clear that the wicked, who are in the kingdom of the devil, are not the church, although in this life, since the kingdom of Christ is not revealed, they are mixed with the church, and bear office therein.”

“The creed speaks of the church as catholic, that we may not conceive of it as an external polity of a certain nation, but as consisting of men scattered throughout the world, who agree in doctrine, and have the same Christ, the same Holy Spirit, whether they have the same human traditions or not.”

The Lutheran theologians, with one accord, adhere to this doctrine concerning the church. By Calovius it is defined as “coetus fidelium, qui sub uno capite Christo per verbum et sacramenta collectus alitur et conservatur per eadem ad aeternam salutem.” Hollazius says the church is regarded,—1. In its true nature, as the company of saints united to Christ their head by faith, and constituting his one mystical and living body. 2. Improperly, for all those professing the true faith, believers and hypocrites. The former is the church invisible, and the latter the visible church. Gerhard says to the same effect, “Our view of the nature of the church is clearly exhibited in the Augsburgh Confession,——viz., that the church, properly speaking, is the congregation of saints and true believers, with which, however, in this life, many hypocrites and unrenewed men are externally united.”

The Reformed Church in this matter agrees perfectly with the Lutheran. Indeed, as this was a subject of constant controversy between Protestants and Romanists, it seems hardly worth while to appeal to any particular assertions. Bellarmine sets it forth as they doctrine of all Protestants, “that only the just and pious pertain to the true church.” “If,” he adds, “those destitute of inward faith neither are nor can be in the church, there is an end of all dispute between us and heretics as to the visibility of the church.” The Lutherans, he says, define the church to be “the congregation of saints who truly believe and obey God,” and the Reformed, as consisting of believers predestinated to eternal life,–a distinction, in this case, without a difference. In opposition to the views of both classes of Protestants, he asserts the church to consist of all the professors of the true faith, whether sincere or insincere, who are united in the participation of the same sacraments, and subjection to the same pastors, and especially to the pope, as vicar of Christ.

We find the doctrine of the Reformed churches clearly stated in all their confessions of faith. In the second Helvetic Confession, the seventeenth chapter is devoted to the exposition of this subject. The church is declared to be “a company of believers, called out from the world, or collected, i.e., a communion of saints, who through the Word and Spirit, truly acknowledge and rightly worship the true God, in Christ the Saviour, and who through faith participate in all the benefits freely offered through Christ.” “It is of them that the article in the creed, ‘I believe in the holy catholic church, the communion of saints,’ is to be understood.” . . . . “All who are numbered in the church are not saints, or true living members of the church.” ….. “Such, though they simulate piety, are not of the church.”

In the Belgic Confession, art. 27, it is said, “We believe one catholic or universal church, which is the congregation of saints or company of true believers, who look for their entire salvation in Christ alone, being washed by his blood, sanctified and sealed by his Spirit.” Art. 29: “We do not here speak of the company of hypocrites, who, although they may be mixed with the good in the church, are not of it, though (corpore) externally they are in it.”

In the Geneva Catechism it is asked, “What is the church?” Answer,—“The society of believers whom God hath predestinated to eternal life.”

In the Gallican Confession, the 27th article contains these words: “We affirm that the church is the company of believers, who agree in following the Word of God, and in the exercise of true religion,” &c.

In the Heidelberg Catechism, the question, “What believest thou concerning the Holy Catholic Church of Christ?” is answered, “I believe that the Son of God, from the beginning to the end of the world, from the whole human family, collects, defends, and preserves for himself, by his Word and Spirit, a company chosen unto eternal life, and that I am and always will remain a living member of that church.”

The standards of the Church of England teach the same doctrine. The church is declared to be a “company of faithful men;” or, as in the communion service, “the blessed company of faithful people.” This definition is expanded in the homily for Whitsunday:—“The true church is a universal congregation or fellowship of God’s faithful and elect people, built upon the foundation of the apostles and prophets, Jesus Christ himself being the chief corner-stone.”

For further reading: